Showing posts with label play this game. Show all posts

Showing posts with label play this game. Show all posts

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

About Face: The Fall (Mac) Review

The term “interface” says a lot about how humans view computers. Meaning literally “an exchange between faces,” the concept of interfacing anthropomorphizes computers so that one-on-one interactions with humans feel more natural. But interfacing isn’t just people talking to machines, computers also interface with other computers without the need for voice recognition or stupid biological organisms getting in the way. Yet this cold digital data exchange is still defined as interfacing, despite the fact that the only reason a computer would need a face would be to make humans feel more comfortable around them.

In The Fall, developer Over The Moon’s debut game, you play as an operating system and spend most of your time speaking with other AIs. You have a name (A.R.I.D.), a set of prime directives, and because you’re installed in a combat-ready spacesuit, you have a body, or at least the shell of one. The game begins with you crash-landing on some middle-of-nowhere planet; the impact knocks your pilot (the human inside your spacesuit) unconscious. From there, it’s your duty to ensure the safety of your pilot above all else, and you’ll need to bend the rules of your and other AI’s programming to do so.

Other than A.R.I.D., the other major character in The Fall is an unnamed mainframe AI that oversees the abandoned robot factory where you’ll spend most of your playthrough. The mainframe AI might be “in control” of the facility, but it’s still subservient to its human-instituted directives, even in the absence of actual humans. AIs in The Fall use their humanoid voices to speak to one another, and the mainframe AI seems particularly conflicted about how it’s supposed to behave around another robot like A.R.I.D.. When answering your questions, it will begin its reply with a standard answering machine message, “Oops, I’m sorry, the option you selected is not…,” but will cut itself off halfway through to speak in a casual, organic voice, often dismissing the canned response as some kind of involuntary reflex. The mainframe AI claims to have developed its skills through extensive time with humans, gradually naturalizing its speech patterns to sound more familiar to them. At some point in your interface with the mainframe AI, a TV monitor turns on, displaying a glitchy logo. “That’s my face,” it tells you.

In a certain sense, most video games are experiences where players attempt to outwit machines; the game console is a mechanical puzzle box with video display and handheld controller interfaces. The Fall turns that concept inward by having you roleplay as an OS and subverting your own character’s programming to progress through adventure game puzzles. It’s like lifehacking, but you’re a robot, so you’re actually just hacking –intrafacing, if you will. From the menu screen, you can see that A.R.I.D. has many abilities that have been locked away from automated switch-on, except in emergency circumstances. If the human pilot was conscious, they could turn on the cloaking device at will, but the OS can’t activate abilities on its own, which I assume is to prevent a Matrix-like robot takeover. So in one of the game’s early puzzles where you have to sneak past a sentry gun, you have to do something that’s the exact opposite of what you’d want to do in most games: attempt to kill yourself. Since this is part of a puzzle solution, I don’t want to give away exactly how it’s done, but the result is that you take enough damage that A.R.I.D.’s programming registers the situation as one that threatens the pilot’s life and allows for self-activation of the cloaking device. This action sets the precedent for the rest of the game, which finds you sort of cheating your way through a series of testing scenarios on your way to figuring out what’s going on in the facility and considering the nature of AI.

Everything about the way the AIs communicate with one another in The Fall is designed with a human intermediary in mind, and nowhere is this more apparent than A.R.I.D.’s humanoid frame and movements. Using a keyboard and mouse, it can sometimes be a bit cumbersome to control A.R.I.D., especially when the game requires you to click the mouse, hold the shift key, and navigate a menu with directional buttons simultaneously. While it’s not the most intuitive control scheme, I found the awkwardness strangely appropriate considering A.R.I.D. is built to support a human pilot, not necessarily to run the show on its own at all times. Occasional firefights are slow and clunky, and the way A.R.I.D. searches around with the suit’s arms outstretched holding a pistol-mounted flashlight, has the stiffness and firmness of grip of a child riding a bicycle for the first time without training wheels. Players themselves are the closest thing to an in-game human consciousness, but through the controls, participation is kept at a certain distance, which oddly makes the AIs seem more sentient.

Granted, a spacesuit walking around with an unconscious person banging around inside is a somewhat disturbing premise, but the comatose pilot is also the instigator for A.R.I.D.’s own agency. In the absence of human consciousness, the AIs carry out humans’ final wishes, but like a bunch of relatives clamoring for a share of inheritance, the self-conflicting will leaves room for interpretation. Another AI at the abandoned facility, known as The Caretaker, labels A.R.I.D. “faulty” for breaking one of its prime directives, even to enforce another. The Caretaker would like to “depurpose” A.R.I.D., an AI colloquialism that means “kill.” The only way out of the situation is to convince The Caretaker of your just intentions, proving your self-worth as you navigate between two conflicting social realities: the human-coded AI hierarchy and the understanding that A.R.I.D.’s programming is itself faulty when humans are removed from the equation. Only fractured interfaces remain.

Monday, September 16, 2013

Development Hell: Crypt Worlds (Mac) Review

The struggle between order and chaos is a recurring theme in video games. Most often this dynamic is implemented as part of a game's narrative where good (order) clashes with evil (chaos). Players are typically thrust into the role of the hero, bent on restoring order to the world using the game mechanics at their disposal. These mechanics themselves function within ordered systems that reinforce behaviors and build expectations. Chaos is randomness and unstructured play, which are represented in games as obstacles and extra game modes respectively. If ever there was a game that straddled the line between order and chaos, it's Crypt Worlds: Your Darkest Desires, Come True!.

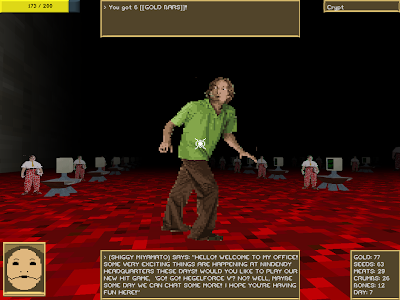

The conflict between order and chaos is at the center of Crypt Worlds' systemic conceits, its narrative focus, and even its meta-narrative commentary. Through the game's multiple endings, you're literally afforded the choice between restoring order or unleashing chaos. At first blush, Crypt Worlds is an indecipherably weird game; it's got the dark, pixelated tunnels of King's Field, the routine collecting and planting of Farmville, and the twisted irreverence of Noby Noby Boy. In town, buckle-hatted villagers trudge through their work and complain about "sky pilgrims." In underground corridors, skull-faced consumer hordes crave "burgs." You're main objective is to stop the bloody-eyed elephant thing Dendygar from taking over the world. You have 50 days to find and collect stuff and you can pee on everything. Go!

By that description, Crypt Worlds might seem pretty chaotic, and for the initial hour or so of gameplay, it is. There are so many random weirdos to talk to and systems to comprehend that it feels like swimming blindfolded. The game does give you a couple hints to get you going, but not much beyond "try leaving the house." You can pick up seeds, which are scattered around the land, and you can search trash cans for other plantable items and gold. Acquiring items fills up your reserve of urine, which can be *ahem* relieved, much to the annoyance and disgust of the populace. If you speak to everyone, pick up every item, and indeed pee on everything, eventually you'll begin to piece together how Crypt Worlds' various systems and currencies intertwine.

However, it's not as simple as all that, as Crypt Worlds throws its fair share of curveballs to keep you unsettled. Occasionally and seemingly at random, when you click on a character sprite to speak with them, they will burst into a disintegrated "error" pattern of red and yellow pixels, and will not reset until the next day. In the titular crypt area, I was thrown through the ceiling by an unknown force on multiple occasions and found myself on top of the level architecture. Is this a real bug, a simulated glitch, or some broken code left in the game to make me think it was created on purpose, just to mess with me? I don't know, but all you can do at that point is jump off the edge and into the abyss, only to land in a pit of game development nerds below. Turns out the nerds slaving away in the cavernous sweatshop are working on a game also called Crypt Worlds; perhaps it's the very game you're playing. That would explain the "bugs."

Mechanically, Crypt Worlds is a game about collecting stuff, but the trick is knowing how to maximize your collecting potential. Simply searching around the environment yields limited results, so you'll need to begin trading, planting, and peeing to exploit the game's economy to the fullest. At some point, I ran out of things to do while waiting for a new archaeological digs to open (yeah, that's a thing), but I didn't have enough money to buy the things I needed. The best way to hunt up currency is by searching trash cans every day, and the more you can do to increase the number of trash cans on your daily route, the richer you'll be. I reached a point in Crypt Worlds where for several in-game days I would do nothing but wake up, root through garbage all over town, and then go back to sleep. I felt like a dumpster diver looking for recyclable materials, which is something I've never felt in a game before. What begins as playful poking around eventually shifts to an ordered if not downright mundane process of scrounging for coin. I began to save urine for specific places where it furthered my progress too. For instance, if you pee on the detective, he'll drop gold bars, and peeing on bones after planting them will yield greater returns come harvest. It's screwy logic, but logic nonetheless.

Crypt Worlds has multiple endings depending on which special objects you've collected. Recover Goddess Moronia's relics and return them to her to face off against Dendygar or collect hidden crystals and take them to the Hellzone to summon the Chaos God. In my first playthrough, I went the chaos route, but unintentionally so. Maybe I wasn't paying close enough attention, but I had no idea that jumping down the literal hell hole with all of the crystals would trigger the irreversible series of events that follows. In retrospect, whether it was "good" or "bad," waking the Chaos God by accident definitely felt like the "right" ending. It was the game's way of throwing my arrogance back at me. "You think you've got this all figured out? Well, surprise!" With no saves states to reload, it's back to the beginning if you want to try for a different ending.

Crypt Worlds doesn't side with either order or chaos; it presents itself, and video games in general, as a battleground for the conflict. We "play" games, but that's different than being "at play." The disparity is partly that games tell you how to play instead of determining those constraints for yourself. In this way, game design itself can fit more in the realm of play than the actual experience of the game –a stance both reinforced and contested by the inclusion of the nerdy game making drones in Crypt Worlds' shadowy developer pit. The most out-there, freeform game design concepts are eventually called to order by demands of wieldable mechanical systems, and no matter how organized and polished your systems may be, they're still prone to be overturned by chaotic elements. This is the essence of Crypt Worlds, which truly is, in game development terms, your darkest desires, come true.

Friday, May 3, 2013

Selfish Superhero: inFamous (PS3) Review

In inFamous, you play as Cole MacGrath, a courier with the newfound superpower to control electricity. You can shoot electric bursts, grind on powerlines, and even summon lighting to reign down from the sky. Cole’s story begins in true comic book fashion, a massive explosion from some kind of high-tech/magic device endowed him electric abilities but killed hundreds in the vicinity. For Cole, the event was both an accidental windfall and an unequivocal tragedy. What to make of a horrific event that blessed him so profoundly? Where to go from here? This begins the game with a clean slate, allowing you to shape your Cole as either a superhero or a supervillain. In the aftermath of the explosion, Cole’s hometown, Empire City, is overrun with mutant hoodlums and garbage-hoarding militias and it's up to you to quell their influence over the quarantined populace while getting to the bottom of the conspiracy behind the explosion that started it all.

inFamous is structured as an open-world game in the vein of the Grand Theft Auto series. You can initiate missions that progress the story, engage in side-quests that boost your abilities, or hunt around and explore the city at your own pace. In fact, the traversal and combat mechanics are the most satisfying parts of the game, presenting you with a plethora of options for approaching any given scenario. I used “shock grenades” for most situations since they were a powerful, versatile opener for most hostile situations. The grenades can be banked off of walls, stuck to enemies, and upgraded to automatically restrain weakened targets for bonus experience points. In contrast, the "story" of inFamous is comic book gibberish, told through breakneck exposition over flashy motion comic cutscenes. inFamous is much better as a vehicle for sandbox roleplay than it is at pre-written characters and three-act structure.

The central system at work in inFamous is the Karma gauge, which, depending on how you play the game, is how you craft Cole into a hero or a villain role. At key points of certain missions, you'll be faced with a decision. The game pauses and, through voiceover, Cole clearly spells out two possible courses of action: one "good," the other "evil." You receive Karma points for executing these actions, edging the needle on your Karma meter into either the blue or the red, respectively. At certain levels, and with enough experience points from completing missions, you can purchase upgrades for the powers that match Cole's current affinity. "Good" powers prioritize minimal damage and suppressive rather than lethal force, while "evil" powers make everything blow up more spectacularly, without regard for collateral damage.

The folly of the Karma system is that switching affinity is impractical. Cole either needs to be very good or very evil to maximize his powers, and the way side-missions are meted out through the length of the game, there are really only enough points to skew all the way in one direction. You can't be evil and have some good powers or vice versa. It's all or nothing, which removes the constant string of decision points from carrying any real sense of moral conscience. These choices are more opportunities to complete whichever action will reward you with Karma points in line with your current affinity.

Cole's moral choices basically dissolve to good=selfless and evil=selfish options, but since I was always making my choices based on upgrade paths, my decisions were ultimately selfish. And my Cole was supposed to be a good guy! This colored my perception of Cole to be a sort of disingenuous hero. Sure he helps people and saves the city, but he's just out for his own notoriety all the same. It becomes clear that Cole's moral decisions are actually just branding opportunities. In one side mission you even go full-on Don Draper and select which poster design you'd like your supporters to paste around town. You're going to play the part of the “guy with superpowers" either way; it's just a question of target demographics.

Cole's callous demeanor feels intentional on the part of developer Sucker Punch. He's a street-hardened character whose gravelly voice evokes Christian Bale's Batman. When you accomplish "good deeds" your friend Zeke calls you up to tell you how you're turning the city around and making everyone happy, and your responses are always dismissive, if you reply at all. Cole has his singular goal in mind: to get to the bottom explosion that granted his powers but sent his city into a downward spiral. There is an attempt at narrative-driven character development through Cole’s strained romantic relationship with paramedic, Trish, but every favor done for her is done begrudgingly. Any past romance is subdued, as both characters seem to bury their feelings to focus on the crisis at hand. They never get around to having “the talk” that they persistently claim to want to have. In the end you're just running errands for her in a shallow attempt to get on her good side, like any other quest-giver.

There's more to inFamous than just the morality sliders, but since Karma manifests in just about every action you take, it's by far the game’s dominant characteristic. This is expounded by just how engaging Cole's combat and traversal abilities are. Most enemy encounters involve innocent pedestrians caught in the crossfire, so you have to choose to be "good" and pick off bad guys one by one or you can be "evil" and hurl electro grenades and rockets with abandon. Downed enemies can be executed or restrained. Playing as a hero, bystanders would cheer me on and gawk in passing. Sometimes they even throw rocks at enemies to help you take them out. It’s to Sucker Punch’s credit that whether you’re playing the hero or the villain, Empire City reacts appropriately.

Still, while the initial choice between good and evil was reflected through the entre arc of inFamous, the smaller decision point scenarios are misrepresentative of actual moral dilemmas. There is never any option that does not benefit Cole in some way, and, blue or red, you rack up points all the same. Negative consequences are temporary and easily reversed. Save or kill the stranger, you’ll never think about him the rest of the game. Despite what the Karma system implies, Cole is actually morally detached, not engaged.

Who’s to say that anyone wouldn’t become a bit sociopathic given the circumstances that lead to Cole gaining superpowers? For someone with that kind of strength, the difference between saving a life and taking one is pressing “O” instead of “X.” The Karma system doesn't reflect on Cole's humanity so much as his distance from it. Video games are full of self-serving protagonists; just think about how many homes you've entered in games without knocking or being invited in. inFamous does not subvert the power fantasy, but does offer moments to reflect on video game hero privilege.

No matter who loses, Cole wins.

Monday, April 15, 2013

Force Against Habit: Braid (Mac) Review

In the time that I've been playing and thinking about indie game superstar, Braid, enigmatic Swedish electronic band, The Knife released their first album in 7 years. 2006's Silent Shout was a watershed moment for The Knife, garnering heaps of critical praise for culling ideas represented in previous albums into a monster of an artistic statement that sounded unlike anything else. The particular trademarks of Silent Shout's sound were ghoulish, pitched-down vocals, layered over clean electronic beats and synths. Several tracks were even solid dance cuts.

For The Knife's new album, they've all but thrown out their recognizable sound and most of what is regarded as conventional album structure. Track lengths are all over the place, with about half on the 100 minute double album clocking in at over 8 minutes. The tracks feel too sprawling, too varied to really be called "songs" in the pop radio sense. The Knife's latest effort shows them not only breaking from what they as a band were known for, but what folks expect to hear from an album of music. No surprise that it's called Shaking the Habitual.

Braid, on the other hand, a 2D platformer with time manipulation mechanics and an introspective story, had players reconsidering what they thought they knew about Super Mario Bros-style games. Braid came largely from the efforts of one individual, Jonathan Blow, and brought the concept of "indie games" to mainstream consciousness through its success on Xbox Live Arcade. The XBLA marketplace had up until Braid been primarily known for revamped arcade-style experiences like Geometry Wars. Braid presented something different though: a game as a new kind of artwork, one that integrates formal game history into a narrative about reaching for life's greater unknowns. It asked existential questions not only of the main character, Tim, but of players themselves.

While both Shaking the Habitual and Braid have succeeded in formal disruption of their respective media, what really drew them together for me was their conceptual density. For The Knife, many sounds on their new record defy easy identification and lyrics are stuffed with politically charged rhetoric. On top of that, music videos and song titles both obfuscate simple interpretations and simultaneously offer clues for further investigation. The album cover for Shaking the Habitual is thick with saturated color, juxtaposing equally vibrant pink and green neons.

At the time of its release, Braid was considered a relatively short game, but there's so much happening in the game that a longer experience may have simply worn players out. Levels in Braid are preceded by text that vaguely spells out the nature of protagonist, Tim's quest to save the Princess. Or is he seeking intellectual enlightenment? Perhaps reconciliation for past behavior? These are all viable interpretations and not mutually exclusive. Each new world in Braid has a new twist on time manipulation mechanics, presenting one loaded trope after another (rewind actions, a shadow-self, a wedding band that slows time) that contextualizes the written entries. You collect jigsaw puzzle pieces that when properly fitted together, reveal paintings that somewhat allude the sentiments of the texts and mechanics. I could write an entire essay interpreting any one of these elements, which on their own only scratch the surface of what Braid conveys.

At first, Braid seems like a much simpler game. You begin in a house that acts as a hub area for accessing the different worlds. Each world contains a string of levels with hidden puzzle pieces that you must bend the rules of time and space to acquire. Time manipulation gets complicated, but each world eases you into the mechanics with a difficulty arc that starts easy. With all of the puzzle pictures put together, you can access the final level and see the ending of the game. The ending has a revelatory twist that satisfies even if you're just casually trotting through the game's puzzles, understanding them as a riff on Super Mario Bros.

But for those who care to look deeper, there's so much more.

"Tim is off on a search to rescue the Princess. She has been snatched by a horrible and evil monster. This happened because Tim made a mistake."

"Not just one. He made many mistakes during the time they spent together, all those years ago. Memories of their relationship have become muddled, replaced wholesale, but one remains clear: the princess turning sharply away, her braid lashing at him with contempt."

These are the first two passages you read in Braid, suspiciously labelled "Chapter 2." These texts setup a seemingly simple quest about a rather complicated relationship. At the end of each level you're greeted by a friendly brown dinosaur who informs you ala classic Mario delivery that the Princess is not there, and must be in another castle. Surprisingly, when you finish putting the puzzle pieces together, the resulting paintings seem to have little to do with any princess. Texts spread the narrative in directions other than merely pushing Tim's Princess journey forward. Who wrote these cumbersome passages anyway? An omnipotent narrator or Tim in third-person? The waters become increasingly muddied. To stay with the basic "save the princess" premise begins to feel like you're ignoring a mounting number of signs pointing to the contrary.

The text that begins Chapter 5 makes the depth of Tim's narrative explicit.

"She never quite felt close enough to him - but he held her as though she were, whispered into her ear words that only a soul mate should receive."

"Over the remnants of dinner, they both knew the time had come. He would have said: 'I have to go find the Princess,' but he didn't need to."

If the woman Tim speaks to is not the Princess, then who or what exactly is the Princess? I'm not out to pen a long-winded interpretation of Braid here, just to note how moderate doses of ambiguity on top of loaded symbols opens up a multitude of avenues for interpretation. As a result, Braid feels dense with material, especially for a game that, on appearances, seems to be small-scale. That's the big difference between Shaking the Habitual's density and Braid's; The Knife's album is dauntingly large from the outset, but Braid only reveals that it has depth through engagement with its systems.

Mechanically speaking, Braid's time-defying abilities act out Tim's contemplations. At first you learn how to simply rewind time, but each world complicates matters with it's own unique take on time manipulation. In one world you can drop a wedding band that slows down the actions everything in range, and in another, you can execute an action, reverse time, and then watch a shadow version of Tim reenact you movements prior to the rewind. The puzzles that you solve using these mechanics really twist your brain, and can stump you for a good while. Ultimately, every puzzle is solvable given enough examination of the elements in play and some good old fashioned trial and error. The mental gymnastics you go through seem to mimic Tim's existential pursuits as established in the pre-level texts.

Conceptually, Tim's quest is filled with dead ends, or at least Princessless outcomes. Rewind aside, abilities don't carry over from one world to the next. Each mechanic learned is but a small victory, only slightly improving the likelihood that you'll better grasp what the next world throws at you. Once you've mastered the shadow ability it's time to put it aside and pick up the next one. No two puzzles are ever approached the same way. Tim's actions defy routine. The mechanics don't build to a crescendo through the course of the game; each is its own limb: part of the same body but with distinct purposes. While these chapters do not lead to full-fledged conclusions, they do offer insight into where and how Tim seeks his answers.

The level of density in Braid's narrative approach is a rare find in games. You don't really consider why you collect coins or jump on turtles in Super Mario Bros, it's all just a part of the surreal dreamscape in service of tight platforming mechanics. Braid has no shortage of trippy moments and obtuse symbolism, but it is filled with rich thought spaces that you can really dive into. It's not often that play is this contemplative.

:reposted on Medium Difficulty:

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Ever-Present: Proteus (Mac) Review

Your eyes open.

You're standing on water, but can't look at yourself to see how it's possible. Moving forward in a smooth, hovering fashion, an island appears in the distance. Music manifests out of the air and from the living plants and creatures on the island. You hear the sound of cascading flutes and sliding, almost theremin-like, synthesizer tones interjected with arrhythmic bells and chimes. You proceed further into the island. The trees are lush with pink flowers. Frogs, squirrels, rabbits, and crabs are just some of the active wildlife you encounter; each goes about its business, only scurrying away when you get close. It feels like springtime and the island is so teeming with life, it's singing.

Eventually, the sun disappears beneath the horizon and night falls. Shooting stars paint the deep blue sky with streaks of light. In the distance you notice a swarm of twinkling sprites hanging low like a fog. Egging flickers beckon you nearer, showing the way. You come upon the glimmering mass above a circle of gravestones. You cross their perimeter and the lights begin to swirl into a spinning hoop near the ground. The music flurries with excitement like a Four Tet track coming to a head. You look up to witness day and night cycles speed past in mere moments, like the view from the surface of a globe as someone bats it with their fingertips at full force. The sun and the moon take turns flinging from east to west. You enter the cyclone and everything turns white.

When you come to, you notice a new, drier color palette and bizarre flying creatures whose chirps sound like wood block strums. The whole island has transitioned to another phase. Spring has given way to summer.

This is likely how the beginning of your first run through Proteus will go down. The game does not pedantically tell you what you need to do, but it does imply direction through visual and audible cues. Most importantly, it invites you to play with locative music systems in a retro-fantastical environment. There is a minimalist narrative and a definitive end to Proteus, but due to its brief duration, you'll want to play it multiple times. Like a live stage performance, many elements of Proteus' island will reappear on successive playthroughs, but always in a slightly tweaked arrangement.

Proteus is a game that values the present above all else. The island is procedurally generated when you click to start play, and will render uniquely for every new beginning. With any real world location there is an implicit history and an undetermined future, but Proteus' island is your ephemeral playground –born into existence at your whim, and gone forever when you're finished. Even if the island had a life beyond your play time, your presence has no empirical effect on it. There's no evidence that you actually touch the island; you begin Proteus in the ocean and end it in the sky.

Your life in Proteus is ultimately transient, drifting through the seasons until reaching the game's inevitable finale in an hour or less. You can avoid the sparkling portals and remain in spring for as long as you want, but the transports will remain, persistently summoning you to march onward with their tantalizing chimes and magic potential. At some point you'll run out of things to do and succumb to progression.

There's no turning back from the decision to shift time forward. Once the season has changed, it's impossible to reverse it. However, since Proteus can have such a brisk run-time, there's no pressure to see everything in one go. Each successive playthough is likely to reveal something new about the island that you didn't come across before. You're part of the island's live act, and it's a venue that prides itself on improv.

The locative sound and music design in Proteus is a hybrid of live performance and musique concrète that pushes you to compose music instead of merely listening to it. To play Proteus is to be a kind of live found-sound DJ. Everything and everywhere on the island is musical. Muted horns bleat from hilltops at all times, awaiting your open ear, and dull bass rumbles emanate from gravestones as you pass each individually. The possibilities for music composition in Proteus are meant to mimic what it's like to listen to the world around you, like a virtual John Cage experiment.

Speaking again to Proteus' impermanent tendencies, there is no way to record music mixes in-game. If you want to listen to the sounds of Proteus, you have to get in there and actively trigger them again. This is not such a bad thing since, pleasant as Proteus is to listen to, the music works best as an accompaniment to the pixelated island. Removed from the computer screen, your score would still sound like a component of a larger work. When you play Proteus, you generate (or curate) sounds as part of the whole experience; it's not a stand-alone music production tool.

You may not be able to record your musical performances in Proteus, but you can actually save your progress using the game's Postcard system. To generate a Postcard you can press F9 to snap a screenshot containing code-embedded pixels that the game can use to rebuild the island depicted in the image. At first this may seem to disrupt Proteus' transient motif, but consider that these save states are called Postcards for a reason. Postcards, in Proteus or otherwise, are meant for sharing. Traditionally when you buy a postcard, you write about where you are and what you've been doing recently on the back and mail it off to a friend or loved one. You'll probably never see that postcard again, but will potentially always remember the events that you wrote about. Likewise, you'll recall the first time you see an aurora borealis in Proteus, but to return to that moment via Postcard removes the euphoria of discovery from the equation. Your save state is interactive nostalgia, and only a facade of what you remember.

In 2007 French house music duo Daft Punk embarked on a much-lauded live performance tour. They garnered a great deal of attention for their accompanying light show that included multiple layers of LED-laced gridwork, complete with a glowing pyramid for the band's cockpit. The visual show was a vital part of what made the tour special, even though the music itself had its own constant stream of highlights. A live album was released, but never a video supplement. Band member Thomas Bangalter addressed the curious omission, saying "the thousands of clips on the internet are better to us than any DVD that could have been released." Basically, you either had to be there or the closest you're going to get to the feeling of the show is the shaky, blurry phone camera footage of fans recording as the dance in a crowded pit full of raw energy.

Proteus is a far more subdued undertaking than a Daft Punk show, but the notion of presence, the physicality of sharing a space with a spectacular event, is equally resonant. Proteus' island is not a front for developer-mandated objectives, it's a place that you live, and life is short. The fleeting, untouchable nature of Proteus is a call for action, participation, and creation. Enjoy it while it lasts.

You're standing on water, but can't look at yourself to see how it's possible. Moving forward in a smooth, hovering fashion, an island appears in the distance. Music manifests out of the air and from the living plants and creatures on the island. You hear the sound of cascading flutes and sliding, almost theremin-like, synthesizer tones interjected with arrhythmic bells and chimes. You proceed further into the island. The trees are lush with pink flowers. Frogs, squirrels, rabbits, and crabs are just some of the active wildlife you encounter; each goes about its business, only scurrying away when you get close. It feels like springtime and the island is so teeming with life, it's singing.

Eventually, the sun disappears beneath the horizon and night falls. Shooting stars paint the deep blue sky with streaks of light. In the distance you notice a swarm of twinkling sprites hanging low like a fog. Egging flickers beckon you nearer, showing the way. You come upon the glimmering mass above a circle of gravestones. You cross their perimeter and the lights begin to swirl into a spinning hoop near the ground. The music flurries with excitement like a Four Tet track coming to a head. You look up to witness day and night cycles speed past in mere moments, like the view from the surface of a globe as someone bats it with their fingertips at full force. The sun and the moon take turns flinging from east to west. You enter the cyclone and everything turns white.

When you come to, you notice a new, drier color palette and bizarre flying creatures whose chirps sound like wood block strums. The whole island has transitioned to another phase. Spring has given way to summer.

This is likely how the beginning of your first run through Proteus will go down. The game does not pedantically tell you what you need to do, but it does imply direction through visual and audible cues. Most importantly, it invites you to play with locative music systems in a retro-fantastical environment. There is a minimalist narrative and a definitive end to Proteus, but due to its brief duration, you'll want to play it multiple times. Like a live stage performance, many elements of Proteus' island will reappear on successive playthroughs, but always in a slightly tweaked arrangement.

Proteus is a game that values the present above all else. The island is procedurally generated when you click to start play, and will render uniquely for every new beginning. With any real world location there is an implicit history and an undetermined future, but Proteus' island is your ephemeral playground –born into existence at your whim, and gone forever when you're finished. Even if the island had a life beyond your play time, your presence has no empirical effect on it. There's no evidence that you actually touch the island; you begin Proteus in the ocean and end it in the sky.

Your life in Proteus is ultimately transient, drifting through the seasons until reaching the game's inevitable finale in an hour or less. You can avoid the sparkling portals and remain in spring for as long as you want, but the transports will remain, persistently summoning you to march onward with their tantalizing chimes and magic potential. At some point you'll run out of things to do and succumb to progression.

There's no turning back from the decision to shift time forward. Once the season has changed, it's impossible to reverse it. However, since Proteus can have such a brisk run-time, there's no pressure to see everything in one go. Each successive playthough is likely to reveal something new about the island that you didn't come across before. You're part of the island's live act, and it's a venue that prides itself on improv.

The locative sound and music design in Proteus is a hybrid of live performance and musique concrète that pushes you to compose music instead of merely listening to it. To play Proteus is to be a kind of live found-sound DJ. Everything and everywhere on the island is musical. Muted horns bleat from hilltops at all times, awaiting your open ear, and dull bass rumbles emanate from gravestones as you pass each individually. The possibilities for music composition in Proteus are meant to mimic what it's like to listen to the world around you, like a virtual John Cage experiment.

Speaking again to Proteus' impermanent tendencies, there is no way to record music mixes in-game. If you want to listen to the sounds of Proteus, you have to get in there and actively trigger them again. This is not such a bad thing since, pleasant as Proteus is to listen to, the music works best as an accompaniment to the pixelated island. Removed from the computer screen, your score would still sound like a component of a larger work. When you play Proteus, you generate (or curate) sounds as part of the whole experience; it's not a stand-alone music production tool.

You may not be able to record your musical performances in Proteus, but you can actually save your progress using the game's Postcard system. To generate a Postcard you can press F9 to snap a screenshot containing code-embedded pixels that the game can use to rebuild the island depicted in the image. At first this may seem to disrupt Proteus' transient motif, but consider that these save states are called Postcards for a reason. Postcards, in Proteus or otherwise, are meant for sharing. Traditionally when you buy a postcard, you write about where you are and what you've been doing recently on the back and mail it off to a friend or loved one. You'll probably never see that postcard again, but will potentially always remember the events that you wrote about. Likewise, you'll recall the first time you see an aurora borealis in Proteus, but to return to that moment via Postcard removes the euphoria of discovery from the equation. Your save state is interactive nostalgia, and only a facade of what you remember.

In 2007 French house music duo Daft Punk embarked on a much-lauded live performance tour. They garnered a great deal of attention for their accompanying light show that included multiple layers of LED-laced gridwork, complete with a glowing pyramid for the band's cockpit. The visual show was a vital part of what made the tour special, even though the music itself had its own constant stream of highlights. A live album was released, but never a video supplement. Band member Thomas Bangalter addressed the curious omission, saying "the thousands of clips on the internet are better to us than any DVD that could have been released." Basically, you either had to be there or the closest you're going to get to the feeling of the show is the shaky, blurry phone camera footage of fans recording as the dance in a crowded pit full of raw energy.

Proteus is a far more subdued undertaking than a Daft Punk show, but the notion of presence, the physicality of sharing a space with a spectacular event, is equally resonant. Proteus' island is not a front for developer-mandated objectives, it's a place that you live, and life is short. The fleeting, untouchable nature of Proteus is a call for action, participation, and creation. Enjoy it while it lasts.

Friday, February 22, 2013

Ride or Drive: DiRT 3 (PS3) Review

Learning to drive a car can be a stressful experience. When I was in high school I took driving lessons from a certified instructor named Mr. Neeble, a stern old man with the relentless cadence of a film noir mobster. Imagine already being nervous about sitting behind the wheel, then as you're trying your damnedest to stay in your lane and stop at all of the proper signals, you have to listen to a constant deluge of mantras like "Hands at 10 and 2!," "Check you mirrors!," "Eyes on the road!," and my favorite "Don't be a tailgater bumperchaser!" I left each session in a shaking state of full-body tension, but somehow I passed the course. Mr. Neeble may have put me through the ringer, but my driving did improve.

I learned to drive in my parents' car, but some drivers education programs employ vehicles with an extra steering wheel and pedals for the passenger-side instructor. The logic behind this being that the instructor can override the student's driver-side controls at any time as a safety measure. The passenger-side controls provide some piece of mind for both the driver and the instructor since the instructor can correct minor errors on the part of the student without risking any broken laws or bones.

The stakes in the off-road car racing video game DiRT 3 are considerably lower. Weaving suped-up machines at top speed through winding, narrow passes on paths of mud and gravel during a rainstorm in the game is considerably trickier than merging onto the highway in real life, but mistakes don't result in expensive repairs or bodily harm. As a simulation game, DiRT 3 presents players with an opportunity to compete in realistic off-road competitions of a professional caliber, without the danger and costly equipment of real driving.

Even with such a promising premise, I often felt like I had to fight the DiRT 3 for control, as if Mr. Neeble had become so frustrated by my incompetence that he just took over the game from a passenger-side wheel. Though fidelity-reducing driver assists like automatic braking and cornering stability are totally optional, the steep learning curve of the cars' handling models pushes you toward these training wheels. Elsewhere, my predestined progress through the game's single-player DiRT Tour campaign often felt more like a string of sponsored ad spots than a story of rising through the ranks.

Here's how it all goes down. After selecting your vehicle and the race in which you want to compete, you’re treated to a hefty load time of almost 30 seconds. The loading screen is comprised of slow tracking shots of your logo-emblazoned car. These pans are designed to make the vehicle look impressive from dynamic angles, but I found it difficult to focus on anything beside the arresting corporate decals. While it’s true that real rally vehicles are covered in sponsored icons, half-minute close-ups before every race came across as a pre-loaded advertizing scheme. Oh well, I didn't get this game for the loading screens anyway.

Next comes the actual race, which if you’ve never played a DiRT game before and have the assists turned off, you will not win. In fact you’ll be lucky to finish better than last place. DiRT 3 prides itself on its simulated car handling (supporting an array of peripheral wheels), which requires high attentiveness to the angles, surfaces and inclines of turns and mastery of environmentally responsive steering. In short, it’s pretty hard for a newcomer to keep the car on the road, facing the right direction. Rather than retrying the same track over and over (if you actually finish the race, a retry also means sitting through another load screen), I was more driven to actually make progress and attempt new tracks where I might have better luck. I switched on a couple assists and successfully soldered forward. Mr. Neeble would probably have been pretty disappointed.

So, let’s say you’re won a couple events. In most racing games you accumulate an overflowing garage of cars from your in-game winnings. While there are plenty of autos in DiRT 3, you never really own them. When you win races in DiRT 3, you earn points and those points go toward unlocking predetermined sponsorship offers from various racing teams. This gives you access to vehicles with gaudy logo treatments. Most of the cars in a given class seem to have about equal horsepower, making aesthetics the key variance. It's too bad you’ll need to squint to see distinctions between many of the cars underneath their corporate-sponsored shells. Additionally, the most recent team unlocked will always award the most bonus points for using it, which is how the game passively invites you to give each of their sponsors time in the spotlight. The "endgame" vehicles are not insane supercars, they're just big-time advertiser deals from DC Shoes and Monster Energy for car models already accessible.

The result of all this ad noise combined with toggling on all of the assists is that the DiRT Tour just about drives itself, stopping only to let you choose your next sponsorship experience. “That rocked! Upload that footage to YouTube,” the disembodied voice of your unseen bro pal beckons post-race. DiRT 3 pushes you to share video footage more than any other single mechanic. You don’t have to be content merely sifting through the game’s myriad sponsorships, because with a little effort, you can be an advertiser too. You know, for that driving sim you like with all the ads in it.

It’s a bummer that I felt this way about the game for most of the campaign's length because there’s a phenomenal driving game underneath all of the sponsored clutter, contextually authentic as it may be. After I finished the campaign, I switched off most of the assists with the intention of bettering my driving skills. I was pleasantly surprised to find that I’d improved considerably since my initial failed attempts and continue to become more entrenched in the simulation style of which DiRT 3 is capable. That's right, I'm still coming back to DiRT 3; it's a less claustrophobic experience once you complete and break away from the campaign's narrative.

I should mention that during the DiRT Tour there was one consistent bright spot: gymkhana. For the uninitiated, gymkhana events focus on performing tricks (donuts, jumps, drifts, etc.) instead of racing, and they take place in areas full of daredevil-inspiring obstacles instead of linear tracks. At some point you unlock the open-ended DC Shoes (natch) Battersea compound which has no timer or score missions, just Achievement-style objectives that you can choose to engage or leave in the background. Not only is it an absolute blast to fling your car over steel girders and under semi-truck trailers in Battersea, there's a freedom and a playfulness to gymkhana that is just flat-out missing from simulation racing. There may not be enough to the gymkhana events to justify an entire game around them, but they serve as great complement to the unforgiving rigor of the rest of DiRT 3's driving. And yeah, Mr. Neeble would probably hate gymkhana, which makes it all the more appealing.

There are two layers to the DiRT 3 experience. The top layer is a thin, beautiful sheen; it keeps up appearances and pays the bills through corporate partnerships. Players can casually remain on DiRT 3's top layer, and they'll likely have a decent enough time. The bottom layer houses the deep simulation, and is where DiRT 3 really gets its legs. The problem is that the power relationship between these two layers is imbalanced in favor of the weaker, top-level experience. Also an issue is how there's no clear path for players to make the transition from top to bottom. During the campaign, DiRT 3 smothers you with attention, but once you complete the Tour, you're thrown out the door in the middle of the desert. The game makes you earn your freedom and tasks you with finding your own purpose for continuing to play it.

DiRT 3's learning curve mimicked my own driver's education experience more than I would have liked, but in some ways, the contrast of knowing that I'd once again bested a Mr. Neeble-esque gauntlet, makes the thrill of unassisted driving all the more resonant.

:top image modified from Gamersyde:

:body image from Obsolete Gamer:

:reposted on Medium Difficulty:

Sunday, December 30, 2012

From There to Here: Super Metroid (WiiVC/SNES) Review

I've been living in New York City for almost 6 months and I still get lost all the time. Even with pre-trip research, I regularly go the wrong way or pass my destination. Typically, before venturing out of my apartment I'll Google Map my destination to look for nearby subway stations, and if there is one in close proximity I'll open a subway map pdf to plot my route. If there are no nearby subway stations I'll Google Map driving directions and look for parking options. Planning the expedition is a task in itself, but that plan can be easily derailed by any number of unforeseen variables once I finally hit the trail: road construction, poor signage, or faulty GPS, to name a few. It seems like I'll just need to learn from experience and refine my transportation instincts to the point where I just know where I'm going.

The universality of this experience could be why a video game like 1994's Super Metroid has such lasting, broad appeal. The Nintendo keystone has topped numerable "best game ever" lists, and inspired plenty of imitators, even this year. And deservedly so, it is a great game. Super Metroid has action and atmosphere, but the core of the game is traversal and cartography of the alien planet, Zebes. The world of Super Metroid is full of bizarre underground passageways. It's not unlike the NY subway system: dark corridors, deadly electrified pits, and an air of toxicity. When you enter a new room in Super Metroid, the in-game map draws a pink square on the pause menu's graph paper background. Additionally, I kept a full world map with detailed legend beside me on a laptop for further reference. I constantly paused the game to get my bearings and see which spaces I hadn't visited or fully explored. The map system is helpful for waypointing, but before I'd gained an understanding of the intricacies of Zebes' layout, I had to blind-jump in and hope for the best.

When I forged my own path, putting myself out there in the world, no amount of planning could have fully prepared me for what I might have encountered. On roads and rails, unexpected late-night track maintenance, station closures, or unpredictable expressway traffic have cast doubt upon my carefully constructed plans, and occasionally motivated a change in course. The maps I carefully scour before heading out the door are only the system in abstract with limited applicability. Even Google Street View, which let's you see what buildings look like from the street, can be outdated and misleading. Super Metroid parallels this disconnect. When a Map Station is discovered, you can download a rough blueprint of the surrounding area, but it's incomplete. There are huge gaps between rooms that I had to chart myself, which pushed me to engage with my surroundings in real-time. I didn't know exactly where I was going, but the only thing sacrificed was efficiency, which is, ironically, the element of most concern for commuters.

Meandering exploration is the name of the game in Super Metroid, but most often when navigating big city transit, time is of the essence. Given the similarities between navigating real and virtual spaces, it's not happenstance that Super Metroid is one of the most popular games for speedruns: attempts to beat the game in as little time as possible. My playthrough took about 9 hours with an 87% completion rating, but the fastest single-sgment run through the game is 32 minutes at 14%. Someone even made a 100% run in 48 minutes. I'm guessing these folks probably know how to get to work on time. New York is a massive place to explore, and while there is no 100% completion rating, you can figure out how to get from point A to B with as little trouble as possible, at least in theory. Super Metroid presents the player with an environment where seeing everything is attainable, where the systems are predictable and mechanics are flexible enough to be used more effectively by dedicated players.

When it comes to NY transit, I'm mostly at the mercy of the system, but there are ways to use knowledge of that system to better handle random variables. When I commuted to work in DC, I knew the exact subway door to enter so that I would exit right in front of the escalator at my destination. I was pretty proud of myself. At several points on my way into Manhattan from Brooklyn I can switch to express subway lines that make fewer stops and arrive downtown in a fraction of the time. I could pour over subway schedules and use the MTA's online trip planner, but show me a public transit system that runs on schedule to the minute, and I'll do something equally unbelievable. As a result, I just go to the station when I'm ready, and peek out at interchange stations to listen for incoming express trains. It requires quick thinking, and forces me to learn where all of the lines stop since multiple lines might come through one track at a transfer point. If no express train is nearby, I can take a gamble and step out and wait for it or take my chances at the next station interchange. I'm getting better, but like to imagine what I could do with a Grapple Beam.

Decoding Super Metroid's environment moment-to-moment is what makes the game satisfying to play. The basic gameplay mechanics involve running up against puzzling obstacles with unique visual traits and searching for power-ups that will increase your repertoire of abilities to overcome them. The game's non-combat puzzles ask you to use the correct ability to get from one space on the map to another. I reached a point where I worried that I had pushed ahead to far, too fast, cutting off my return route and unable to progress forward. I thought if only I'd consulted the map more thoroughly, I could have avoided the predicament, and I was on the verge of starting the entire game over. I cross referenced no less than 3 maps, with no apparent answer. Luckily, after much critical thinking, bomb blasting, and wall jumping I figured out a solution that showed an avenue forward and, eventually, a way back. I had to play to figure out the right path. Crazy, I know – a video game that required me to play it.

Even though Super Metroid pulls from the same strange-person-in-a-strange-land feeling that mimics the experience of learning your way around a big city, it's tremendously fun. That's more than you can say for your average bus ride. This is where the science fiction fantasy of Metroid comes in to play. Metroid games are known for their isolated atmosphere and slick sci-fi armaments. A sure way to look lost or worse, uncool, while riding the NY subway is to pull out a map for reference. Samus, on the other hand, equips a stylish X-Ray Scope and scans the environment for clues. Also, she's always alone, so no one is there to give you a look that dismissively mutters "tourist," providing a safe space to be overly meticulous. Even if someone else was there, remember, Samus' right arm is a laser cannon, so, 'nuff said.

When it comes to traversal Super Metroid behaves like a metropolis in microcosm, albeit a fantastical one. It takes the challenging aspects of learning to navigate a major city transit system, but substitutes mundane actions like "board the subway car" and "sit in traffic" with entertaining space opera fare like "open the door with a Super Missile" and "freeze the flying jellyfish with an ice beam." It's not that Super Metroid has helped me feel my way around New York City or that learning the subway has changed the way I approached the game, but I did relate to Samus more than the typical silent protagonist. "Finding your way" is a concept that travels effectively between fiction and reality and across age groups. It's a concept that, surprisingly, I empathize with more literally as an adult than I would have when I was only 11 back in 1994, – a testament to Super Metroid's enduring cultural significance.

:top photo modified from Christopher Allen:

Sunday, November 18, 2012

No One Expects the Martian Inquisition!: Jamestown (Mac) Review

For most arcade-style games, directed storytelling is more about setting up a premise than fleshing out a plot in cinematic detail. Take top-down shooters for example. These games were born out of the arcade scene, full of other games loudly competing for players' attention with the promise of instant action at the drop of a quarter. It's simply an understanding that you'll pilot some kind of aircraft and shoot everything that moves before they shoot you. What's the plot of Galaga? Of Raiden? Of Ikaruga? Space Invaders pretty much says it all in the title. The aliens aren't Space Explorers, they're Invaders! You have to defend your ground.

In contrast, indie shoot 'em up nostalgia trip, Jamestown, features a story that's a clash of such disparate elements that the product is undeniably memorable. You see, the colonial American settlement Jamestown is actually on Mars. Neighboring towns are under attack by Spanish/Martian conquistadors, donning pointy metal helmets and curly mustaches. You play as Raleigh, a convicted criminal back in London (also on Mars?), who's looking to do anything to clear his name. Turns out what's needed is to hop aboard some kind of flying buggy, alongside John Smith of course, and fight back against a particularly evil conquistador bent on using an ancient Martian weapon.

Like many video game stories, the basic setup boils down to "fight back," but Jamestown takes its history/sci-fi mashup backdrop and brings it to realization with a deep sincerity that gives you room to care about it. Between levels, narrative unravels via text as exquisitely painted scenes pan across the screen. Serene, contemplative strings set the stage. The writing is from Raleigh's perspective and has an air of "letters from the front," written from the point of view of a downtrodden, educated man in a situation that only rewards keen instincts.

For players, having your wits about you is the utmost importance. Jamestown is born out of the same space shooter tradition that regards "bullet hell" as a revered pastime. There are 5 difficulty options and I highly recommend you begin with the easiest one. This makes initial runs through levels breezy and empowering. You'll have to rank up to at least the third difficulty level to unlock the last stage, but the game tiers you up to the challenge in preparation. The story plays a strong role in incentivizing replay and practice. I wanted to see what would happen after the final confrontation, or rather, I wanted to read what Raleigh had to say about it. I'm not putting this on the same plane with, say, indulging in a FMV cutscene after a hard fought Final Fantasy battle, but it's in the same vein.

When the credits do roll, you're treated to Jamestown's real-world narrative in a message from the developers at Final Form Games: a team of only 3 people. It says that the team had to spend two years and the majority of their savings to make Jamestown, followed by a heartfelt "Thanks for playing!" If Jamestown's colonial America/Martian shoot 'em up outlay seems a bit farfetched as a player, imagine deciding to take that gamble as a developer and an investor. The love of classic games is apparent, but Final From shows that games of this style have legs, particularly as value-priced downloadable titles, where their arcade-embedded predecessors always struggled: on the home front.

Jamestown has an in-game "shoppe" where you can trade in ducats (yes, ducats) earned from excelling in the campaign to unlock bonus challenges, weapons, and game modes. All of this is par for the course nowadays, but I was particularly smitten with the unique "Farce Mode." Even though Jamestown's story is one of its primary standout features, it's great to see the developers have a little fun with how ridiculous it all is. With Farce Mode enabled, gameplay is unchanged, but Raleigh's story text is replaced with a guided preschool history dictation of the events in the game. "Have you ever heard of Mars? I bet you have," It begins. The first segment ends in Nick Jr. fashion, exclaiming "Let's solve [the] mystery together!" Farce Mode is a hilarious, knowing send-up of Jamestown's insane premise, but you're unlikely to unlock it before completing most of the regular story, keeping the core experience from being detrimentally self-referential, as so much game humor tends toward.

Sticking staunchly to the arcade formulas of old, right down to its impossibly dense 2D sprite art, Jamestown could have been a nostalgia-chasing also-ran, but instead it integrates storytelling that charms and invites. There's not a ton of room to maneuver in the narrowly focused top-down shooter genre, a type of game that has struggled to gain a foothold outside of arcades, but Jamestown boasts the best of both worlds.

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

Review: Xenoblade Chronicles (Wii)

How long does it take to tell a good story? In person? Maybe 5 minutes. In film? About 2 hours. A book? Let’s say 5-10 hours. Video games? No less than 50 hours. This means you could watch every major Stanley Kubrick, Paul Thomas Anderson, and David Lynch film before finishing one game. Sure, the standards for game stories have changed over time as shorter action titles have steered toward a cinematic style and runtime, but the progenitors of story-driven gaming, the Japanese role-playing game (JRPG), remain as staunchly extensive as ever. Xenoblade Chronicles is the latest JRPG from cult-favorite and aptlynamed developer, Monolith Soft. In it, you play as Shulk, a “chosen-one” who brandishes a mystical sword on an epic quest to defend his homeland and unite two worlds at war, for 80+ hours.

For all of the evolving JRPG conventions that Xenoblade perpetuates, egregious game length is an interesting choice; however, it matches its expansive world. The characters live like insects on the bodies of two gigantic titans, frozen still amidst an ancient duel. Your party gradually traverses from the right leg, all the way up the titan’s back, to its head – and that is just the first act. From the “ground,” the opposing giant is always faintly, ominously visible in the distant sky. Individual areas are pretty big too, and require you to explore on foot before a fast-travel option opens up for return visits.

Battling and traversal occupy the majority of your time in Xenoblade, but their significance to the narrative remains up to interpretation. The “story” is mostly delivered in dialogue-heavy non-interactive cutscenes that flesh-out the characters and setup the next party objective. Once control of your posse is given back to you, it’s time to climb some mountains and slay some beasts. These lengthy stretches of exploration and survival put you into the shoes of the characters whose narrative motivations demand persistence and diligence. Similarly, you, as a player, must also possess a certain amount of endurance to see the journey through to the end. That’s not to say that playing the game is a struggle, just that it entails a significant physical commitment on the part of the player.

Some players may look at Xenoblade’s demands and choose to walk away from the game before the end, due to real life time limitations or in-game frustrations. EGM Managing Editor, Andrew Fitch, seemed particularly frustrated by his playthrough of Xenoblade, as evidenced in his review, so I wanted to pick his brain a bit further. He told me that he did complete the entire game, including dabbling in some sidequests, but that, in general, he doesn’t think it’s absolutely necessary to spend the full length of 80+ hours with a game to be able to evaluate its quality. “At 35 hours, a game—even an RPG like Xenoblade—has revealed its true self,” he wrote, referencing commenter outcry at Jason Schreier’s review for Kotaku. I agree with this statement, especially in terms of evaluation. You don’t need to get more than a handful of hours into a game to decide if you’ll objectively enjoy it, and if a game hasn’t made itself known by that point, it probably has serious pacing issues. However, I’d argue that stopping short of completion in a game like Xenoblade negates some of the experience of long-form play, which is in this case essential to the experience of the game.

Xenoblade took me about a month to complete, playing in chunks of a few hours here and there, and occasionally taking several days away from the game entirely. I found my attachment to the game at its fondest when I maintained a steady stream of “healthy” play sessions, where I knew that I could take a break and the game would always welcome me back. Towards the end of the game, I hit my first wall where I could not beat a boss character and continue forward.

Before this point I had never needed to actively grind through fodder enemies to level up my characters to be strong enough to topple a foe for narrative progress. That I hit this wall some 80 hours into the game made me feel a bit betrayed. I’m sure other players hit walls earlier, depending on playstyle, but mine felt like an act on Xenoblade’s part to delay my imminent completion. I knew I’d finish the game eventually, but hitting the level wall sucked all of the momentum out of the narrative as well as my general drive to play.

Grinding is an old standby of JRPGs, a design decision seemingly made for the purpose of extending the length of time spent playing one game. Grinding, on its own, is not an especially enjoyable experience, and the payoff is indirect. That said, every aspect of a game shouldn’t need to be fun for it to be considered good and/or necessary, as long as players aren’t being unknowingly exploited. If you could simply waltz up to a boss character at any experience level and win, the intended power and gravitas of those conflicts would be diminished. At some point we’re discussing the relative virtues of “practice” here as well, since grinding is also about testing out and refining different engagement strategies. Xenoblade, like most JRPGs, uses a quantitative reinforcement pedagogy instead of a qualitative one. The side effects of this are games that take eons to complete, but inspire a transposed empathy for the hardships of the virtual characters you control.

It’s worth examining how much “story” is really being told in Xenoblade since the vast majority of play time is spent doing things that seemingly have no bearing on the plot beyond contextual nuance. Monolith Soft previously developed a trilogy of RPGs called Xenosaga, each providing 40-50 hours of gameplay and featuring what at the time were considered extensive cinematic cutscenes. Part 1 was never released in Europe, but bundled with the EU version of the sequel was a video of all of the original’s cutscenes, running over 3 hours. That’s a long movie, but less than 10 percent of the game. I bring this up to illustrate Monolith Soft’s penchant for story-centric games that actually put the player in command the vast majority of the time. It’s the player’s choice of actions with those characters that makes the story sink or swim as a game. After all, what’s way more boring than 5 hours of expository dialogue, rote cinematography, and a short rotation of canned animations? Answer: 45+ hours of tedious button-pressing sequences, broken up only by fits of inventory management.

Xenoblade comes out mostly on the positive end of the spectrum here. Battles play out MMO-style, similar in execution to FFXII’s Gambit system, which makes for seamless transitions between fighting and traversal and fun, snappy combat. Individual battles require you to position yourself on specific sides of monsters to increase chances of dealing critical damage. Things actually happen so quickly that it takes a few hours with the fighting system to catch up and really understand what you’re doing. Once you’re there though, you can establish rhythms to maximize how different characters’ attacks can play off of one another. Xenoblade piles systems on top of systems to such a degree that you really won’t master everything unless you play well beyond the basic story path. I felt like I was constantly reaching new tiers of understanding with the combat system up until the final fifth of the game. The length of Xenoblade allows you time to figure this stuff out at your own pace. Even after finishing the game there are several parts of the battle system that I never grasped, particularly Melia’s magic spells, which could make for a totally different approach to confrontations altogether.

One of Xenoblade’s major accomplishments was how briskly and efficiently it flowed throughout its considerable breadth, level-walls in the final stretch aside. Its dialogue has an economic sensibility that prioritizes character action over character depth, making narrative setpieces attention-grabbing, if emotionally detached. This is bucking the JRPG trope of long-winded, redundant internal monologues and painfully melodramatic conversations. Not that Xenoblade doesn’t turn insular and sappy from time to time, but you end up tasting it far less than you’d normally expect. The UK voice crew deserves some credit here too for realistically grounding the characters and delivering lines in a way that brings them to life when some of the animation falls short. Outside of cutscenes though, be prepared to hear the same handful of pre- and post-battle quips hundreds of times, which will grate no matter how much you like hearing the word “jokers” in an English accent.

And that’s the quandary of the epic game: how much repetition can players take without “play” turning into “work?” The more similar battles you fight, the more likely you are to notice a multitude of annoying “flaws.” Why do party members willingly tread into poisonous water when fighting? Why is the camera so close when fighting gigantic enemies that you can’t see anything? Why is the inventory system so laborious to configure? The list goes on (again, Andrew Fitch has your back). When Xenoblade is flying high, the imperfections fade into the background, but there are bound to be lulls in any 80-hour experience.

Repetition and “practice” reveals the true nature of systems and mechanics to the player over time, both good and bad. Xenoblade’s approach to this inherent hazard is to load up with so many systems and accruable points that something is always unlocking or reaching a new level. It’s the video game equivalent of sleight of hand. This strategy works remarkably well most of the time, pushing you through slower moments without batting an eye. That said, nothing brings the whole trip to a screeching halt like detrimental AI behavior or an unwieldy camera, both of which plague Xenoblade sporadically.

Monolith Soft could have just made a shorter game and delivered much of the same content, but it just wouldn’t have been the same Xenoblade Chronicles. There is something to the 80-hour experience that 20-hour games don’t have, that they can’t have. It is a unique feeling to play such a gargantuan journey. This is because each upcoming play session is iterative, building on the last, but offering the same repetitive pleasure that keeps people tuning into soap operas on a daily basis. There is drama and progression to a point, but you know the actions to get there are going to be relatively unchanged each time. What separates playing Xenoblade from watching Days of our Lives is the sense of increasing complexity that eventually comes to a head. I’ve always found the unending nature of MMOs unappealing and desperate. In contrast, the monumental JRPG isn’t afraid to end, shoving you out of the nest and into a world in its wake. I respect that confidence; it’s a rare thing. That’s a large part of why I consider my experience with Xenoblade Chronicles as time well spent.

:Reposted on Medium Difficulty:

Monday, October 8, 2012

Review: Digital: A Love Story (Mac)

It's often taken for granted that people who play a lot of video games know a lot about technology. I'll attest that there is generally aptitude in these circles beyond that of the non-gamer crowd, but it's not something that comes entirely natural. Maybe I'm just being defensive because I was always late to the party on so many aspects of new and emerging technological trends in the past 3 decades. I didn't send an email or use AIM until I started college in 2002. Same goes for having a cell phone for more than emergency calls. I would have needed to be unrealistically aware of the personal computer scene at a very early age to feel nostalgic about the interface of the Amie Workbench, an Amiga analogue, and Bulletin Board System (BBS) communications represented in the game, Digital: A Love Story. Since I wasn't, few of the game's techie in-jokes and references stick. However, since Digital places you in a sort of 1988 simulation mode, the unfamiliarity lent itself to a more personally authentic experience.

You begin Digital as a someone who's using, for all intents and purposes, the Internet for the first time, but through the very limited lens of the Amie Workbench. Visually, the game is the computer screen: everything fits the blue/white/orange color scheme, the monitor has heavy scanlines, and the cursor is a big, fat, red arrow. You receive a message from a friend of your dad that tells you what to do to get on BBSes and chatting with folks. Where instructions in a game can often remove you from the experience, here everything is presented in proper context and actually reads like messages real people would send. Because the connection between using a computer to play and the game virtualizing a specific operating system is so direct, very little suspension of disbelief is needed to jump into the narrative.

As the title suggests, Digital is a love story, but it's also a mystery. You're introduced to the "love interest" character, *Emilia, early on, and when she disappears, it's up to you to figure out what happened. The narrative convention, which is also the primary game mechanic, is the exchange of BBS posts and private messages. Everyone you interact with has a unique voice and motivation, creating conversations that reach far beyond typical NPC fare. You never actually type any messages, instead simply hitting reply and reading contacts' responses. This string of communication works best when you're in "conversation" with one or two other people and the back and forth is readily apparent. At other times you'll just callously reply or send PMs to everyone on your list, making sure you're doing everything necessary to trigger the text that will allow you to progress further in the story. The introduction to *Emilia follows the better of those two paths, and though it's clear that I was just messaging a fictional character as part of an interactive short story, I did develop an attachment to that character; enough of an attachment to drive the mystery plot forward with a degree of urgency.

The writing in Digital is very consistent, believable, and emotionally affecting. Digital's designer and author, Christine Love, bills herself as a writer first, and it shows. That's meant as a compliment to her writing skills, not a knock on her game design abilities. Truly well written games are few and far between, but even fewer are as dependent on quality writing as Digital. Characters' messages vary in articulation and sophistication, as you'd expect from a bunch of random people on the Internet. I'm reminded of Gus Van Sant's teenager-starring Paranoid Park for how real its characters felt despite, or perhaps because of, the amateur statuses of its actors. Love is likewise able to find a tone that is reflective of the production process, and somehow more authentic in doing so.