Showing posts with label mac. Show all posts

Showing posts with label mac. Show all posts

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

About Face: The Fall (Mac) Review

The term “interface” says a lot about how humans view computers. Meaning literally “an exchange between faces,” the concept of interfacing anthropomorphizes computers so that one-on-one interactions with humans feel more natural. But interfacing isn’t just people talking to machines, computers also interface with other computers without the need for voice recognition or stupid biological organisms getting in the way. Yet this cold digital data exchange is still defined as interfacing, despite the fact that the only reason a computer would need a face would be to make humans feel more comfortable around them.

In The Fall, developer Over The Moon’s debut game, you play as an operating system and spend most of your time speaking with other AIs. You have a name (A.R.I.D.), a set of prime directives, and because you’re installed in a combat-ready spacesuit, you have a body, or at least the shell of one. The game begins with you crash-landing on some middle-of-nowhere planet; the impact knocks your pilot (the human inside your spacesuit) unconscious. From there, it’s your duty to ensure the safety of your pilot above all else, and you’ll need to bend the rules of your and other AI’s programming to do so.

Other than A.R.I.D., the other major character in The Fall is an unnamed mainframe AI that oversees the abandoned robot factory where you’ll spend most of your playthrough. The mainframe AI might be “in control” of the facility, but it’s still subservient to its human-instituted directives, even in the absence of actual humans. AIs in The Fall use their humanoid voices to speak to one another, and the mainframe AI seems particularly conflicted about how it’s supposed to behave around another robot like A.R.I.D.. When answering your questions, it will begin its reply with a standard answering machine message, “Oops, I’m sorry, the option you selected is not…,” but will cut itself off halfway through to speak in a casual, organic voice, often dismissing the canned response as some kind of involuntary reflex. The mainframe AI claims to have developed its skills through extensive time with humans, gradually naturalizing its speech patterns to sound more familiar to them. At some point in your interface with the mainframe AI, a TV monitor turns on, displaying a glitchy logo. “That’s my face,” it tells you.

In a certain sense, most video games are experiences where players attempt to outwit machines; the game console is a mechanical puzzle box with video display and handheld controller interfaces. The Fall turns that concept inward by having you roleplay as an OS and subverting your own character’s programming to progress through adventure game puzzles. It’s like lifehacking, but you’re a robot, so you’re actually just hacking –intrafacing, if you will. From the menu screen, you can see that A.R.I.D. has many abilities that have been locked away from automated switch-on, except in emergency circumstances. If the human pilot was conscious, they could turn on the cloaking device at will, but the OS can’t activate abilities on its own, which I assume is to prevent a Matrix-like robot takeover. So in one of the game’s early puzzles where you have to sneak past a sentry gun, you have to do something that’s the exact opposite of what you’d want to do in most games: attempt to kill yourself. Since this is part of a puzzle solution, I don’t want to give away exactly how it’s done, but the result is that you take enough damage that A.R.I.D.’s programming registers the situation as one that threatens the pilot’s life and allows for self-activation of the cloaking device. This action sets the precedent for the rest of the game, which finds you sort of cheating your way through a series of testing scenarios on your way to figuring out what’s going on in the facility and considering the nature of AI.

Everything about the way the AIs communicate with one another in The Fall is designed with a human intermediary in mind, and nowhere is this more apparent than A.R.I.D.’s humanoid frame and movements. Using a keyboard and mouse, it can sometimes be a bit cumbersome to control A.R.I.D., especially when the game requires you to click the mouse, hold the shift key, and navigate a menu with directional buttons simultaneously. While it’s not the most intuitive control scheme, I found the awkwardness strangely appropriate considering A.R.I.D. is built to support a human pilot, not necessarily to run the show on its own at all times. Occasional firefights are slow and clunky, and the way A.R.I.D. searches around with the suit’s arms outstretched holding a pistol-mounted flashlight, has the stiffness and firmness of grip of a child riding a bicycle for the first time without training wheels. Players themselves are the closest thing to an in-game human consciousness, but through the controls, participation is kept at a certain distance, which oddly makes the AIs seem more sentient.

Granted, a spacesuit walking around with an unconscious person banging around inside is a somewhat disturbing premise, but the comatose pilot is also the instigator for A.R.I.D.’s own agency. In the absence of human consciousness, the AIs carry out humans’ final wishes, but like a bunch of relatives clamoring for a share of inheritance, the self-conflicting will leaves room for interpretation. Another AI at the abandoned facility, known as The Caretaker, labels A.R.I.D. “faulty” for breaking one of its prime directives, even to enforce another. The Caretaker would like to “depurpose” A.R.I.D., an AI colloquialism that means “kill.” The only way out of the situation is to convince The Caretaker of your just intentions, proving your self-worth as you navigate between two conflicting social realities: the human-coded AI hierarchy and the understanding that A.R.I.D.’s programming is itself faulty when humans are removed from the equation. Only fractured interfaces remain.

Monday, September 16, 2013

Development Hell: Crypt Worlds (Mac) Review

The struggle between order and chaos is a recurring theme in video games. Most often this dynamic is implemented as part of a game's narrative where good (order) clashes with evil (chaos). Players are typically thrust into the role of the hero, bent on restoring order to the world using the game mechanics at their disposal. These mechanics themselves function within ordered systems that reinforce behaviors and build expectations. Chaos is randomness and unstructured play, which are represented in games as obstacles and extra game modes respectively. If ever there was a game that straddled the line between order and chaos, it's Crypt Worlds: Your Darkest Desires, Come True!.

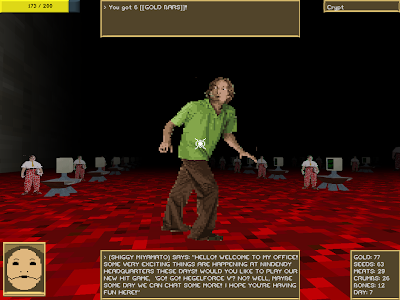

The conflict between order and chaos is at the center of Crypt Worlds' systemic conceits, its narrative focus, and even its meta-narrative commentary. Through the game's multiple endings, you're literally afforded the choice between restoring order or unleashing chaos. At first blush, Crypt Worlds is an indecipherably weird game; it's got the dark, pixelated tunnels of King's Field, the routine collecting and planting of Farmville, and the twisted irreverence of Noby Noby Boy. In town, buckle-hatted villagers trudge through their work and complain about "sky pilgrims." In underground corridors, skull-faced consumer hordes crave "burgs." You're main objective is to stop the bloody-eyed elephant thing Dendygar from taking over the world. You have 50 days to find and collect stuff and you can pee on everything. Go!

By that description, Crypt Worlds might seem pretty chaotic, and for the initial hour or so of gameplay, it is. There are so many random weirdos to talk to and systems to comprehend that it feels like swimming blindfolded. The game does give you a couple hints to get you going, but not much beyond "try leaving the house." You can pick up seeds, which are scattered around the land, and you can search trash cans for other plantable items and gold. Acquiring items fills up your reserve of urine, which can be *ahem* relieved, much to the annoyance and disgust of the populace. If you speak to everyone, pick up every item, and indeed pee on everything, eventually you'll begin to piece together how Crypt Worlds' various systems and currencies intertwine.

However, it's not as simple as all that, as Crypt Worlds throws its fair share of curveballs to keep you unsettled. Occasionally and seemingly at random, when you click on a character sprite to speak with them, they will burst into a disintegrated "error" pattern of red and yellow pixels, and will not reset until the next day. In the titular crypt area, I was thrown through the ceiling by an unknown force on multiple occasions and found myself on top of the level architecture. Is this a real bug, a simulated glitch, or some broken code left in the game to make me think it was created on purpose, just to mess with me? I don't know, but all you can do at that point is jump off the edge and into the abyss, only to land in a pit of game development nerds below. Turns out the nerds slaving away in the cavernous sweatshop are working on a game also called Crypt Worlds; perhaps it's the very game you're playing. That would explain the "bugs."

Mechanically, Crypt Worlds is a game about collecting stuff, but the trick is knowing how to maximize your collecting potential. Simply searching around the environment yields limited results, so you'll need to begin trading, planting, and peeing to exploit the game's economy to the fullest. At some point, I ran out of things to do while waiting for a new archaeological digs to open (yeah, that's a thing), but I didn't have enough money to buy the things I needed. The best way to hunt up currency is by searching trash cans every day, and the more you can do to increase the number of trash cans on your daily route, the richer you'll be. I reached a point in Crypt Worlds where for several in-game days I would do nothing but wake up, root through garbage all over town, and then go back to sleep. I felt like a dumpster diver looking for recyclable materials, which is something I've never felt in a game before. What begins as playful poking around eventually shifts to an ordered if not downright mundane process of scrounging for coin. I began to save urine for specific places where it furthered my progress too. For instance, if you pee on the detective, he'll drop gold bars, and peeing on bones after planting them will yield greater returns come harvest. It's screwy logic, but logic nonetheless.

Crypt Worlds has multiple endings depending on which special objects you've collected. Recover Goddess Moronia's relics and return them to her to face off against Dendygar or collect hidden crystals and take them to the Hellzone to summon the Chaos God. In my first playthrough, I went the chaos route, but unintentionally so. Maybe I wasn't paying close enough attention, but I had no idea that jumping down the literal hell hole with all of the crystals would trigger the irreversible series of events that follows. In retrospect, whether it was "good" or "bad," waking the Chaos God by accident definitely felt like the "right" ending. It was the game's way of throwing my arrogance back at me. "You think you've got this all figured out? Well, surprise!" With no saves states to reload, it's back to the beginning if you want to try for a different ending.

Crypt Worlds doesn't side with either order or chaos; it presents itself, and video games in general, as a battleground for the conflict. We "play" games, but that's different than being "at play." The disparity is partly that games tell you how to play instead of determining those constraints for yourself. In this way, game design itself can fit more in the realm of play than the actual experience of the game –a stance both reinforced and contested by the inclusion of the nerdy game making drones in Crypt Worlds' shadowy developer pit. The most out-there, freeform game design concepts are eventually called to order by demands of wieldable mechanical systems, and no matter how organized and polished your systems may be, they're still prone to be overturned by chaotic elements. This is the essence of Crypt Worlds, which truly is, in game development terms, your darkest desires, come true.

Friday, July 19, 2013

Meta-Mega-Retro: Kavinsky (Mac/iOS) Review

There is no shortage of nostalgia-mining, 80s-pop-culture-referencing, neon-soaked video games these days. From Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon to Hotline Miami to Double Dragon Neon, many new games are taking their cues from 1980s film, music, and games themselves and repackaging those design choices into new experiences of varying quality and originality. Now, French electro music producer Kavinsky has entered the fray with his own self-titled game, featuring a mixture of brawling and driving segments, largely composed of the same "80s" tropes that have come before.

Kavinsky's music and the fictional character of Kavinsky, a Ferrari-driving zombie from 1986, already pull heavily from 80s aesthetics, so adapting that premise into video game form makes a certain kind of logical sense. Kavinsky the game has a handful of levels (it's available for free) that alternate between Stretts of Rage-style beat 'em up stages and timed driving segments where you're outrunning thugs or cops. In fact, the Kavinksy mythos already draws so heavily from decades-old material that as a game, it's difficult to distinguish original ideas from all the well-worn references.

Before the Kavinsky game existed, the producer's music videos shed some light on his character's backstory through short vignettes of dramatic action: a car accident, a chase, a staredown, an escape, a revival. In the game, those individual shots are drawn out into levels that mostly just reinforce the original thrills through repetition, which in turn makes them less thrilling over time. Kavinsky the game is also sillier than the music videos which portray themselves with the self-seriousness that actual 80s action movies and games did. Is it impossible to use tropes from the 80s in earnest without a wink and nod to make fun of their own premise? I don't know, but that said, my favorite thing about Kavinsky is one of the sillier parts of the game: cigarettes and beer are health pick-ups and they look an awful lot like Marlboros and Budweisers for which official licenses have certainly not been acquired. Smoking to gain health is funny because it's ironic and also stereotypically French. It's a gag about Kavinsky the character, not a joke told in reference to a bygone decade.

To enjoy your time with Kavinsky is to seek out those small touches, because everything else only adds up to a reskinned version of the games it's referencing. The brawler levels are basically Final Fight stages, down to the named mohawk-donning street toughs. Unfortunately Kavinsky does not control as well as Cody did back in '89. Each punch slides Kavinsky forward, often forcing you to gradually turn as you go to keep him in line. There is also no blocking, jumping, or any real strategy needed beyond mashing the punch button until the bad guys fall down. There's no reason to use the slower kick move at all except in tandem with "punch" to trigger a furious supermove when you have a full combo meter.

The driving levels are typical point-to-point time challenges in the vein of Rad Racer, right down to the red Ferrari and the Grand Canyon track. The difference is, Kavinsky isn't about racing, it's just about going. There's very little to detrimentally crash into and no need to acknowledge the brake pedal. In fact, Kavinsky's car auto-accelerates by default, making it feel less like you're "one with the car" and more like you're trying your best to keep a possessed, squirrelly vehicle pointing in the right direction. The Ferrari's neon blue trim and streaking tail lights end up looking way more badass than you actually feel behind the wheel.

Ultimately, even if Kavinsky comes off a bit loose, disjointed, and indebted to it's 80s callbacks, it succeeds at evoking the spirit of its namesake in video game form. In 2010, another French producer, Danger, released a trailer for his latest EP, showing the intro to a 16-bit video game created just for the promotion. As far as I know, that game does not actually exist, but that didn't stop me from guessing how it would play and wishing I could get my hands on it. The fact that a playable Kavinsky game exists is a cool thing in and of itself. Kavinsky may not be a standout example of fighting or driving mechanics, but it is a fun concept carried out to thorough execution.

--

Notes on the iOS version of Kavinsky: The brawling portions of the game use an on-screen joystick and buttons, and the driving levels use tilt controls by default. Both of these control schemes are less than ideal and make simple movements in the game frustrating. There are also two additional levels in the touchscreen versions of the game where you defend your parked Ferrari from waves of thugs. These stages use augmented reality, pulling the live images from your mobile device's camera to create the "ground" for the level to take place upon. Unfortunately my iPhone requires me to hold it in the bottom corners in order to use the on-screen joystick, putting my left hand's fingers in front of the camera. When the game looses sight of the original "ground" image, it stops the game and waits for you to find it again. Maybe these levels would work on devices that have a different location for their camera, but in my case, they were more-or-less unplayable. If possible, I'd recommend playing Kavinsky on a computer instead.

Monday, April 15, 2013

Force Against Habit: Braid (Mac) Review

In the time that I've been playing and thinking about indie game superstar, Braid, enigmatic Swedish electronic band, The Knife released their first album in 7 years. 2006's Silent Shout was a watershed moment for The Knife, garnering heaps of critical praise for culling ideas represented in previous albums into a monster of an artistic statement that sounded unlike anything else. The particular trademarks of Silent Shout's sound were ghoulish, pitched-down vocals, layered over clean electronic beats and synths. Several tracks were even solid dance cuts.

For The Knife's new album, they've all but thrown out their recognizable sound and most of what is regarded as conventional album structure. Track lengths are all over the place, with about half on the 100 minute double album clocking in at over 8 minutes. The tracks feel too sprawling, too varied to really be called "songs" in the pop radio sense. The Knife's latest effort shows them not only breaking from what they as a band were known for, but what folks expect to hear from an album of music. No surprise that it's called Shaking the Habitual.

Braid, on the other hand, a 2D platformer with time manipulation mechanics and an introspective story, had players reconsidering what they thought they knew about Super Mario Bros-style games. Braid came largely from the efforts of one individual, Jonathan Blow, and brought the concept of "indie games" to mainstream consciousness through its success on Xbox Live Arcade. The XBLA marketplace had up until Braid been primarily known for revamped arcade-style experiences like Geometry Wars. Braid presented something different though: a game as a new kind of artwork, one that integrates formal game history into a narrative about reaching for life's greater unknowns. It asked existential questions not only of the main character, Tim, but of players themselves.

While both Shaking the Habitual and Braid have succeeded in formal disruption of their respective media, what really drew them together for me was their conceptual density. For The Knife, many sounds on their new record defy easy identification and lyrics are stuffed with politically charged rhetoric. On top of that, music videos and song titles both obfuscate simple interpretations and simultaneously offer clues for further investigation. The album cover for Shaking the Habitual is thick with saturated color, juxtaposing equally vibrant pink and green neons.

At the time of its release, Braid was considered a relatively short game, but there's so much happening in the game that a longer experience may have simply worn players out. Levels in Braid are preceded by text that vaguely spells out the nature of protagonist, Tim's quest to save the Princess. Or is he seeking intellectual enlightenment? Perhaps reconciliation for past behavior? These are all viable interpretations and not mutually exclusive. Each new world in Braid has a new twist on time manipulation mechanics, presenting one loaded trope after another (rewind actions, a shadow-self, a wedding band that slows time) that contextualizes the written entries. You collect jigsaw puzzle pieces that when properly fitted together, reveal paintings that somewhat allude the sentiments of the texts and mechanics. I could write an entire essay interpreting any one of these elements, which on their own only scratch the surface of what Braid conveys.

At first, Braid seems like a much simpler game. You begin in a house that acts as a hub area for accessing the different worlds. Each world contains a string of levels with hidden puzzle pieces that you must bend the rules of time and space to acquire. Time manipulation gets complicated, but each world eases you into the mechanics with a difficulty arc that starts easy. With all of the puzzle pictures put together, you can access the final level and see the ending of the game. The ending has a revelatory twist that satisfies even if you're just casually trotting through the game's puzzles, understanding them as a riff on Super Mario Bros.

But for those who care to look deeper, there's so much more.

"Tim is off on a search to rescue the Princess. She has been snatched by a horrible and evil monster. This happened because Tim made a mistake."

"Not just one. He made many mistakes during the time they spent together, all those years ago. Memories of their relationship have become muddled, replaced wholesale, but one remains clear: the princess turning sharply away, her braid lashing at him with contempt."

These are the first two passages you read in Braid, suspiciously labelled "Chapter 2." These texts setup a seemingly simple quest about a rather complicated relationship. At the end of each level you're greeted by a friendly brown dinosaur who informs you ala classic Mario delivery that the Princess is not there, and must be in another castle. Surprisingly, when you finish putting the puzzle pieces together, the resulting paintings seem to have little to do with any princess. Texts spread the narrative in directions other than merely pushing Tim's Princess journey forward. Who wrote these cumbersome passages anyway? An omnipotent narrator or Tim in third-person? The waters become increasingly muddied. To stay with the basic "save the princess" premise begins to feel like you're ignoring a mounting number of signs pointing to the contrary.

The text that begins Chapter 5 makes the depth of Tim's narrative explicit.

"She never quite felt close enough to him - but he held her as though she were, whispered into her ear words that only a soul mate should receive."

"Over the remnants of dinner, they both knew the time had come. He would have said: 'I have to go find the Princess,' but he didn't need to."

If the woman Tim speaks to is not the Princess, then who or what exactly is the Princess? I'm not out to pen a long-winded interpretation of Braid here, just to note how moderate doses of ambiguity on top of loaded symbols opens up a multitude of avenues for interpretation. As a result, Braid feels dense with material, especially for a game that, on appearances, seems to be small-scale. That's the big difference between Shaking the Habitual's density and Braid's; The Knife's album is dauntingly large from the outset, but Braid only reveals that it has depth through engagement with its systems.

Mechanically speaking, Braid's time-defying abilities act out Tim's contemplations. At first you learn how to simply rewind time, but each world complicates matters with it's own unique take on time manipulation. In one world you can drop a wedding band that slows down the actions everything in range, and in another, you can execute an action, reverse time, and then watch a shadow version of Tim reenact you movements prior to the rewind. The puzzles that you solve using these mechanics really twist your brain, and can stump you for a good while. Ultimately, every puzzle is solvable given enough examination of the elements in play and some good old fashioned trial and error. The mental gymnastics you go through seem to mimic Tim's existential pursuits as established in the pre-level texts.

Conceptually, Tim's quest is filled with dead ends, or at least Princessless outcomes. Rewind aside, abilities don't carry over from one world to the next. Each mechanic learned is but a small victory, only slightly improving the likelihood that you'll better grasp what the next world throws at you. Once you've mastered the shadow ability it's time to put it aside and pick up the next one. No two puzzles are ever approached the same way. Tim's actions defy routine. The mechanics don't build to a crescendo through the course of the game; each is its own limb: part of the same body but with distinct purposes. While these chapters do not lead to full-fledged conclusions, they do offer insight into where and how Tim seeks his answers.

The level of density in Braid's narrative approach is a rare find in games. You don't really consider why you collect coins or jump on turtles in Super Mario Bros, it's all just a part of the surreal dreamscape in service of tight platforming mechanics. Braid has no shortage of trippy moments and obtuse symbolism, but it is filled with rich thought spaces that you can really dive into. It's not often that play is this contemplative.

:reposted on Medium Difficulty:

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Ever-Present: Proteus (Mac) Review

Your eyes open.

You're standing on water, but can't look at yourself to see how it's possible. Moving forward in a smooth, hovering fashion, an island appears in the distance. Music manifests out of the air and from the living plants and creatures on the island. You hear the sound of cascading flutes and sliding, almost theremin-like, synthesizer tones interjected with arrhythmic bells and chimes. You proceed further into the island. The trees are lush with pink flowers. Frogs, squirrels, rabbits, and crabs are just some of the active wildlife you encounter; each goes about its business, only scurrying away when you get close. It feels like springtime and the island is so teeming with life, it's singing.

Eventually, the sun disappears beneath the horizon and night falls. Shooting stars paint the deep blue sky with streaks of light. In the distance you notice a swarm of twinkling sprites hanging low like a fog. Egging flickers beckon you nearer, showing the way. You come upon the glimmering mass above a circle of gravestones. You cross their perimeter and the lights begin to swirl into a spinning hoop near the ground. The music flurries with excitement like a Four Tet track coming to a head. You look up to witness day and night cycles speed past in mere moments, like the view from the surface of a globe as someone bats it with their fingertips at full force. The sun and the moon take turns flinging from east to west. You enter the cyclone and everything turns white.

When you come to, you notice a new, drier color palette and bizarre flying creatures whose chirps sound like wood block strums. The whole island has transitioned to another phase. Spring has given way to summer.

This is likely how the beginning of your first run through Proteus will go down. The game does not pedantically tell you what you need to do, but it does imply direction through visual and audible cues. Most importantly, it invites you to play with locative music systems in a retro-fantastical environment. There is a minimalist narrative and a definitive end to Proteus, but due to its brief duration, you'll want to play it multiple times. Like a live stage performance, many elements of Proteus' island will reappear on successive playthroughs, but always in a slightly tweaked arrangement.

Proteus is a game that values the present above all else. The island is procedurally generated when you click to start play, and will render uniquely for every new beginning. With any real world location there is an implicit history and an undetermined future, but Proteus' island is your ephemeral playground –born into existence at your whim, and gone forever when you're finished. Even if the island had a life beyond your play time, your presence has no empirical effect on it. There's no evidence that you actually touch the island; you begin Proteus in the ocean and end it in the sky.

Your life in Proteus is ultimately transient, drifting through the seasons until reaching the game's inevitable finale in an hour or less. You can avoid the sparkling portals and remain in spring for as long as you want, but the transports will remain, persistently summoning you to march onward with their tantalizing chimes and magic potential. At some point you'll run out of things to do and succumb to progression.

There's no turning back from the decision to shift time forward. Once the season has changed, it's impossible to reverse it. However, since Proteus can have such a brisk run-time, there's no pressure to see everything in one go. Each successive playthough is likely to reveal something new about the island that you didn't come across before. You're part of the island's live act, and it's a venue that prides itself on improv.

The locative sound and music design in Proteus is a hybrid of live performance and musique concrète that pushes you to compose music instead of merely listening to it. To play Proteus is to be a kind of live found-sound DJ. Everything and everywhere on the island is musical. Muted horns bleat from hilltops at all times, awaiting your open ear, and dull bass rumbles emanate from gravestones as you pass each individually. The possibilities for music composition in Proteus are meant to mimic what it's like to listen to the world around you, like a virtual John Cage experiment.

Speaking again to Proteus' impermanent tendencies, there is no way to record music mixes in-game. If you want to listen to the sounds of Proteus, you have to get in there and actively trigger them again. This is not such a bad thing since, pleasant as Proteus is to listen to, the music works best as an accompaniment to the pixelated island. Removed from the computer screen, your score would still sound like a component of a larger work. When you play Proteus, you generate (or curate) sounds as part of the whole experience; it's not a stand-alone music production tool.

You may not be able to record your musical performances in Proteus, but you can actually save your progress using the game's Postcard system. To generate a Postcard you can press F9 to snap a screenshot containing code-embedded pixels that the game can use to rebuild the island depicted in the image. At first this may seem to disrupt Proteus' transient motif, but consider that these save states are called Postcards for a reason. Postcards, in Proteus or otherwise, are meant for sharing. Traditionally when you buy a postcard, you write about where you are and what you've been doing recently on the back and mail it off to a friend or loved one. You'll probably never see that postcard again, but will potentially always remember the events that you wrote about. Likewise, you'll recall the first time you see an aurora borealis in Proteus, but to return to that moment via Postcard removes the euphoria of discovery from the equation. Your save state is interactive nostalgia, and only a facade of what you remember.

In 2007 French house music duo Daft Punk embarked on a much-lauded live performance tour. They garnered a great deal of attention for their accompanying light show that included multiple layers of LED-laced gridwork, complete with a glowing pyramid for the band's cockpit. The visual show was a vital part of what made the tour special, even though the music itself had its own constant stream of highlights. A live album was released, but never a video supplement. Band member Thomas Bangalter addressed the curious omission, saying "the thousands of clips on the internet are better to us than any DVD that could have been released." Basically, you either had to be there or the closest you're going to get to the feeling of the show is the shaky, blurry phone camera footage of fans recording as the dance in a crowded pit full of raw energy.

Proteus is a far more subdued undertaking than a Daft Punk show, but the notion of presence, the physicality of sharing a space with a spectacular event, is equally resonant. Proteus' island is not a front for developer-mandated objectives, it's a place that you live, and life is short. The fleeting, untouchable nature of Proteus is a call for action, participation, and creation. Enjoy it while it lasts.

You're standing on water, but can't look at yourself to see how it's possible. Moving forward in a smooth, hovering fashion, an island appears in the distance. Music manifests out of the air and from the living plants and creatures on the island. You hear the sound of cascading flutes and sliding, almost theremin-like, synthesizer tones interjected with arrhythmic bells and chimes. You proceed further into the island. The trees are lush with pink flowers. Frogs, squirrels, rabbits, and crabs are just some of the active wildlife you encounter; each goes about its business, only scurrying away when you get close. It feels like springtime and the island is so teeming with life, it's singing.

Eventually, the sun disappears beneath the horizon and night falls. Shooting stars paint the deep blue sky with streaks of light. In the distance you notice a swarm of twinkling sprites hanging low like a fog. Egging flickers beckon you nearer, showing the way. You come upon the glimmering mass above a circle of gravestones. You cross their perimeter and the lights begin to swirl into a spinning hoop near the ground. The music flurries with excitement like a Four Tet track coming to a head. You look up to witness day and night cycles speed past in mere moments, like the view from the surface of a globe as someone bats it with their fingertips at full force. The sun and the moon take turns flinging from east to west. You enter the cyclone and everything turns white.

When you come to, you notice a new, drier color palette and bizarre flying creatures whose chirps sound like wood block strums. The whole island has transitioned to another phase. Spring has given way to summer.

This is likely how the beginning of your first run through Proteus will go down. The game does not pedantically tell you what you need to do, but it does imply direction through visual and audible cues. Most importantly, it invites you to play with locative music systems in a retro-fantastical environment. There is a minimalist narrative and a definitive end to Proteus, but due to its brief duration, you'll want to play it multiple times. Like a live stage performance, many elements of Proteus' island will reappear on successive playthroughs, but always in a slightly tweaked arrangement.

Proteus is a game that values the present above all else. The island is procedurally generated when you click to start play, and will render uniquely for every new beginning. With any real world location there is an implicit history and an undetermined future, but Proteus' island is your ephemeral playground –born into existence at your whim, and gone forever when you're finished. Even if the island had a life beyond your play time, your presence has no empirical effect on it. There's no evidence that you actually touch the island; you begin Proteus in the ocean and end it in the sky.

Your life in Proteus is ultimately transient, drifting through the seasons until reaching the game's inevitable finale in an hour or less. You can avoid the sparkling portals and remain in spring for as long as you want, but the transports will remain, persistently summoning you to march onward with their tantalizing chimes and magic potential. At some point you'll run out of things to do and succumb to progression.

There's no turning back from the decision to shift time forward. Once the season has changed, it's impossible to reverse it. However, since Proteus can have such a brisk run-time, there's no pressure to see everything in one go. Each successive playthough is likely to reveal something new about the island that you didn't come across before. You're part of the island's live act, and it's a venue that prides itself on improv.

The locative sound and music design in Proteus is a hybrid of live performance and musique concrète that pushes you to compose music instead of merely listening to it. To play Proteus is to be a kind of live found-sound DJ. Everything and everywhere on the island is musical. Muted horns bleat from hilltops at all times, awaiting your open ear, and dull bass rumbles emanate from gravestones as you pass each individually. The possibilities for music composition in Proteus are meant to mimic what it's like to listen to the world around you, like a virtual John Cage experiment.

Speaking again to Proteus' impermanent tendencies, there is no way to record music mixes in-game. If you want to listen to the sounds of Proteus, you have to get in there and actively trigger them again. This is not such a bad thing since, pleasant as Proteus is to listen to, the music works best as an accompaniment to the pixelated island. Removed from the computer screen, your score would still sound like a component of a larger work. When you play Proteus, you generate (or curate) sounds as part of the whole experience; it's not a stand-alone music production tool.

You may not be able to record your musical performances in Proteus, but you can actually save your progress using the game's Postcard system. To generate a Postcard you can press F9 to snap a screenshot containing code-embedded pixels that the game can use to rebuild the island depicted in the image. At first this may seem to disrupt Proteus' transient motif, but consider that these save states are called Postcards for a reason. Postcards, in Proteus or otherwise, are meant for sharing. Traditionally when you buy a postcard, you write about where you are and what you've been doing recently on the back and mail it off to a friend or loved one. You'll probably never see that postcard again, but will potentially always remember the events that you wrote about. Likewise, you'll recall the first time you see an aurora borealis in Proteus, but to return to that moment via Postcard removes the euphoria of discovery from the equation. Your save state is interactive nostalgia, and only a facade of what you remember.

In 2007 French house music duo Daft Punk embarked on a much-lauded live performance tour. They garnered a great deal of attention for their accompanying light show that included multiple layers of LED-laced gridwork, complete with a glowing pyramid for the band's cockpit. The visual show was a vital part of what made the tour special, even though the music itself had its own constant stream of highlights. A live album was released, but never a video supplement. Band member Thomas Bangalter addressed the curious omission, saying "the thousands of clips on the internet are better to us than any DVD that could have been released." Basically, you either had to be there or the closest you're going to get to the feeling of the show is the shaky, blurry phone camera footage of fans recording as the dance in a crowded pit full of raw energy.

Proteus is a far more subdued undertaking than a Daft Punk show, but the notion of presence, the physicality of sharing a space with a spectacular event, is equally resonant. Proteus' island is not a front for developer-mandated objectives, it's a place that you live, and life is short. The fleeting, untouchable nature of Proteus is a call for action, participation, and creation. Enjoy it while it lasts.

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Proteus' Photogenic Landscape

I've been playing and thinking a lot about Proteus. In addition to a review I intend to write (done), I also discuss the game's musical systems in a forthcoming piece for Kill Screen (also done). Player-driven sound composition is the driving force behind Proteus' incentive to explore, but it's visuals deserve special recognition as well. I'm burned out on pixel art, but Proteus' mixture of flat-shaded polygons, gradient-laden color fields, and always-facing-you sprites hits a nice balance; no 8-bit nostalgia required.

I primarily play video games on consoles, but when I do play on my Mac, I like to take screenshots. Sure I use them in blog posts, but I also just enjoy in-game photography. With IRL cameras, landscape photography is not my thing, but Proteus presents such strikingly beautiful vistas, I couldn't resist.

After I'd already taken the shots you'll find below, I learned about Proteus' Postcard feature, where you can take screenshots using the F9 key. The resulting png files also have data embedded in one of their corners so the game can recreate the world from the image. This means if you run across a rare weather occurrence, you can both snap a dynamic picture and a shareable save state all at once. It's pretty neat.

Again, unfortunately none of my images are Postcards, but I didn't think I could recreate these same images on a new island so I'm sharing them as is. Enjoy.

Saturday, December 8, 2012

What's This Do?: McPixel (Mac) Review

Before you can navigate the top menu in the blocky point n' click adventure game, McPixel, you're faced with a brief gameplay scenario. Your character, the titular McPixel, stands in a field awaiting your orders. In the center of the screen is a big red button with a giant arrow pointing to it that reads "Press to start." There is no way to continue in the game without giving in to the temptation of the button, so you click it, like so many Wile E. Coyotes who have come before. Instantly, a boulder falls from the sky, crushing McPixel and everything else on screen. The main menu then pops up and you're free to select game modes and fiddle with the options as you'd normally expect. In this short little introductory scene, McPixel let's you know exactly what kind of game it is: a cartoonish, old-school adventure game with a sophomoric sense of humor.

The premise of McPixel is a twisted joke itself. As the player, you click around in screen-sized areas to interact with objects in hope of defusing a bomb, but often you'll click on the wrong object, triggering a quick animated gag before the whole scene explodes. Seemingly derived from SNL's MacGruber skits about an inept bomb-defusing action star (itself a spoof of the late 80s TV action series, MacGyver), McPixel plays it's own influences up for laughs. It's a bit like that part in Multiplicity where Michael Keaton clones himself so many times that the quality of his copies turn out a bit...unflattering. It's true that McPixel's major "plot" conceit, like the Macs from which it's derived, is still bomb disarmament, but it's the clone that came out very wrong. That may be a long walk to take for the concept of a game that primarily trades in fart jokes, but a funny juxtaposition in its own way.

Mechanically, McPixel is a conventional point n' click adventure game, but because of it's short-fuse timer and rapid level cycling, it feels quite different from other genre entries. McPixel's levels are divided into subsets of six that you tackle in rotation. You're only given 15 seconds per scenario to make a definitive action before the bomb explodes and the scene shifts to the next level in the group. Adventure games are traditionally known for their slow pace, smart writing, and lengthy inventory-based puzzles. McPixel dials up the speed, substitutes writing for Dumb and Dumber-esque visual punchlines, and makes combining the incorrect objects part of the fun. It's true that you can find yourself stuck on a puzzle, rewatching incrementally less amusing gags play out multiple times, but you'll be onto the next set before too long. This rapid-fire approach is an appealing recipe for someone like myself who needs an extra push to get my interest up for a point n' click adventure.

Juvenile humor combined with the act of "daring" McPixel to put himself in compromising situations is at the heart of McPixel's appeal. With 15 seconds to solve puzzles, you can spend your time clicking on things that you think will disable the ever-present bomb, or you can click random stuff that you want McPixel to mess around with before inevitably being blown to bits. The character McPixel is quite a gullible dolt, succumbing to the mildest of peer pressure, all for your amusement. McPixel's base-level instinct is usually to kick whatever you click on, which rarely ends well for him. Policeman? Kick 'em! Stick of dynamite? Kick it! In one scene you're presented with a hair dryer, a yeti, and a barrel with a lit fuse. You could click on the barrel in hopes that you put the fuse out somehow, but you'd probably rather see what happens when McPixel tries to blow dry a yeti.

Ironically, sometimes going for the sight gags ends up disarming the bomb anyway, leading you to question your judgement about whether the obvious solution is too obvious to be the real answer. McPixel plays with this nonsensical logic throughout its length, at times requiring you to pursue a ridiculous pair of actions (two clicks at most) to diffuse a bomb, but other times the solution is as simple as clicking on a bomb in clear view to swiftly win the level. Note that if you can get a character to consume the explosive, it will probably detonate in their body, puffing out their stomach like a balloon, but ultimately saving the stage from annihilation. With this precedent established, McPixel's play incentive stems from a desire to view all of the comedic possibilities, regardless of whether the bomb gets taken care of or not. Plus, since the only way to earn 100% completion on a level and unlock bonus areas is to witness every joke in a scene, you'll spend a considerable chunk of your time with McPixel hunting them all down.

Make no mistake, McPixel's humor is as dumb as it gets, but it still made me chuckle from time to time. The game goes lowbrow, but sticks mostly to slaphappy, cartoonish violence and bodily functions, instead of wading into dark or offensive territory. Granted, someone might find the bonus level set inside a toilet offensive, but it's all quite tame in the grand scheme of internet-borne comedy. It helps that the visual style of McPixel is, well, pixelated to such an extreme degree, reinforcing its harmlessly crude nature. The character McPixel is nothing but a dead-eyed, pot-bellied stack of red and blue squares, and the rest of the resident populace is rendered in similar MS Paint fashion. McPixel is full of nerd-culture references that look great/terrible in the game's chunky, low resolution world too. The whole game comes off a bit like an overly-compressed JPEG version of MAD Magazine.

Like most middle-school humor, you'll probably reach a point where McPixel's jokes begin fall flat and the thinking behind them becomes too transparent to enjoy with your initial enthusiasm. If you play McPixel for more than one suite of levels at a time, you risk stretching the appeal of the game's comedy beyond its limits, but in small doses, it's the interactive syndicated comic strip that your local paper would run if they had the technology and weren't opposed to jokes about public urination. The same way a comic like Marmaduke is really just the same two punchlines repeated ad infinitum, McPixel also offers mere variation on a handful of gags. At their core though, those jokes are still so stupid that they're pretty funny. McPixel may not have perfected the accessible adventure comedy game, but it does step in a progressively-minded, if aesthetically dim-witted, direction.

Sunday, November 18, 2012

No One Expects the Martian Inquisition!: Jamestown (Mac) Review

For most arcade-style games, directed storytelling is more about setting up a premise than fleshing out a plot in cinematic detail. Take top-down shooters for example. These games were born out of the arcade scene, full of other games loudly competing for players' attention with the promise of instant action at the drop of a quarter. It's simply an understanding that you'll pilot some kind of aircraft and shoot everything that moves before they shoot you. What's the plot of Galaga? Of Raiden? Of Ikaruga? Space Invaders pretty much says it all in the title. The aliens aren't Space Explorers, they're Invaders! You have to defend your ground.

In contrast, indie shoot 'em up nostalgia trip, Jamestown, features a story that's a clash of such disparate elements that the product is undeniably memorable. You see, the colonial American settlement Jamestown is actually on Mars. Neighboring towns are under attack by Spanish/Martian conquistadors, donning pointy metal helmets and curly mustaches. You play as Raleigh, a convicted criminal back in London (also on Mars?), who's looking to do anything to clear his name. Turns out what's needed is to hop aboard some kind of flying buggy, alongside John Smith of course, and fight back against a particularly evil conquistador bent on using an ancient Martian weapon.

Like many video game stories, the basic setup boils down to "fight back," but Jamestown takes its history/sci-fi mashup backdrop and brings it to realization with a deep sincerity that gives you room to care about it. Between levels, narrative unravels via text as exquisitely painted scenes pan across the screen. Serene, contemplative strings set the stage. The writing is from Raleigh's perspective and has an air of "letters from the front," written from the point of view of a downtrodden, educated man in a situation that only rewards keen instincts.

For players, having your wits about you is the utmost importance. Jamestown is born out of the same space shooter tradition that regards "bullet hell" as a revered pastime. There are 5 difficulty options and I highly recommend you begin with the easiest one. This makes initial runs through levels breezy and empowering. You'll have to rank up to at least the third difficulty level to unlock the last stage, but the game tiers you up to the challenge in preparation. The story plays a strong role in incentivizing replay and practice. I wanted to see what would happen after the final confrontation, or rather, I wanted to read what Raleigh had to say about it. I'm not putting this on the same plane with, say, indulging in a FMV cutscene after a hard fought Final Fantasy battle, but it's in the same vein.

When the credits do roll, you're treated to Jamestown's real-world narrative in a message from the developers at Final Form Games: a team of only 3 people. It says that the team had to spend two years and the majority of their savings to make Jamestown, followed by a heartfelt "Thanks for playing!" If Jamestown's colonial America/Martian shoot 'em up outlay seems a bit farfetched as a player, imagine deciding to take that gamble as a developer and an investor. The love of classic games is apparent, but Final From shows that games of this style have legs, particularly as value-priced downloadable titles, where their arcade-embedded predecessors always struggled: on the home front.

Jamestown has an in-game "shoppe" where you can trade in ducats (yes, ducats) earned from excelling in the campaign to unlock bonus challenges, weapons, and game modes. All of this is par for the course nowadays, but I was particularly smitten with the unique "Farce Mode." Even though Jamestown's story is one of its primary standout features, it's great to see the developers have a little fun with how ridiculous it all is. With Farce Mode enabled, gameplay is unchanged, but Raleigh's story text is replaced with a guided preschool history dictation of the events in the game. "Have you ever heard of Mars? I bet you have," It begins. The first segment ends in Nick Jr. fashion, exclaiming "Let's solve [the] mystery together!" Farce Mode is a hilarious, knowing send-up of Jamestown's insane premise, but you're unlikely to unlock it before completing most of the regular story, keeping the core experience from being detrimentally self-referential, as so much game humor tends toward.

Sticking staunchly to the arcade formulas of old, right down to its impossibly dense 2D sprite art, Jamestown could have been a nostalgia-chasing also-ran, but instead it integrates storytelling that charms and invites. There's not a ton of room to maneuver in the narrowly focused top-down shooter genre, a type of game that has struggled to gain a foothold outside of arcades, but Jamestown boasts the best of both worlds.

Saturday, November 3, 2012

Review: BIT.TRIP RUNNER (Mac)

Prerequisite: check out this video of an individual demonstrating their mastery of the game/toy Bop It. It's best if you watch the whole thing, but I understand if you become impatient and bail early. BIT.TRIP RUNNER is a video game version of Bop It. No, it's not an official tie-in, but the mechanics are transferred nearly verbatim. In RUNNER you control a character who must dodge obstacles as the environment force-scrolls past. Directional buttons trigger block, kick, slide, and vault actions while the spacebar executes a jump. These moves are sort-of tied in to the accompanying music score, but mostly you rely on visual discernment to time and select your actions. Like Bop It, one false move while playing will stop you in your tracks and force you to try again from the beginning. Also like Bop It, you can beat and master RUNNER, but doing so is like learning to play a song that no one wants to listen to on an instrument that doesn't really exist.

When it came time for me to decide what I wanted to play in my grade school band, I chose percussion. Drumming seemed more fun than brass or woodwinds, but I was also more confident in my ability to keep a beat over maintaining melody. My sister took piano lessons, which I was encouraged to take as well, but never did. We got a programmable electric piano at home eventually, and rather than actually play conventional music, I'd setup the percussion kit that assigned individual drums and cymbals to specific keys and make all sorts of noise. There was also a neat trick you could do by pressing two low-octave "square lead" keys at the same time, producing some pretty satisfying bass rumbles. I own a MPC drum machine, though it's been sorely underused. I adore Rez and was a die-hard DDR player for several years. In short, though I would not call myself a musician of any kind, I know my way around button/key-based beat making. On its surface, I should love BIT.TRIP RUNNER.

Unfortunately for me, RUNNER plays how I always feared piano lessons would go: demanding, unforgiving, and with a slavish dedication to someone else's creativity rather than my own. In RUNNER, you can't study notes on a page to prepare, you must react in real time and memorize the level's patterns through failure. At most, you have a full second to recognize what object is heading your way and tap the appropriate key to evade or deflect. Each time you screw up, it's like the piano instructor wraps your knuckles with a ruler and points to the first note on the sheet. If you play a piano piece correctly, you enjoy the satisfaction of hard-earned accomplishment along with the joy of hearing a song that you presumably like. In RUNNER, you just earn arbitrary points and the music you've produced only occasionally sounds like a song. There is no level editor or any way of really getting hands-on with the mechanics beyond the prescribed courses.

People have compared RUNNER to mobile games like Canabalt and Temple Run for their similar, forced running perspectives. Both Canabalt and Temple Run use randomized obstacles and challenge players to get farther than their previous attempt, but as far as I'm aware, neither has endpoints. RUNNER is broken up into 36 preset levels, and withholds progression until you complete the stage prior. The big difference between RUNNER and something like Canabalt is how you feel after triggering a fail state. With Canabalt it feels like the game playfully dares you to try it again. You know losing is inevitable, but it's fun to try and get farther than last time. In fact, "losing" isn't really "losing," it's just the end of the round. Retries in RUNNER are instantaneous. If you forget to kick a box on cue, the game zips you back to the start of the stage, and after a brief moment you're back on your way again. I applaud Gaijin Games for making the process so snappy, but subsequent runs feel more like a matter of survival than heartfelt attempts on the part of the player. You're trapped in the gameplay loop until you either win or cry "uncle" and quit.

There are collectable gold bars throughout RUNNER that encourage a more daring style of play, but the game doesn't offer rewards that merit the effort required to snatch them all. If you do collect every gold bar in a level you can play a bonus Pitfall-styled area, which is neat a couple times, but not 30+. You only get one try at the bonus levels per completion of a regular stage, which means you may have spent a half hour trying to get a perfect run, only for your "prize" to last a fleeting handful of seconds. The numerous retries on regular levels pushed me to ignore the gold bars as much as I could, eliminating several tricky maneuvers from my regimen, but also rendering the music more spartan, lacking the distinctive chimes emitted by grabbing the bars. You could interpret the game as an incisive metaphor for the daily, 9-5 grind perpetuated by an uncompromising capitalist economy, but that's an unearned credit. Instead, playing BIT.TRIP RUNNER feels like a really difficult motor skills exam – something for the sport stacking set.

I'm being pretty hard on RUNNER, but it does have its merits. Visually, the game renders Atari 2600 graphics as 3D cubic blocks to grinning, stylistic effect. If you collect enough point multipliers in a level, an old-school Activision rainbow will tail behind the titular runner as it goes – RUNNER's incentivization at its most effective. Mechanically, the game is as sharp as it gets. Though it asks for tight precision, failure is never the result of ambiguous design. I could knock the effectiveness of RUNNER's musical implementation, but having listened to the soundtrack outside of the game, their track selection is appropriate and catchy. Lastly, I began this review by comparing RUNNER to Bop It, but I should point out that I actually like Bop It. It's a party icebreaker game that asks players to focus their attention, likely in a social situation that requires otherwise – a humorous juxtaposition. As an unfortunate point of contrast, there just isn't much to laugh about in RUNNER.

Still, there are clearly a lot of people who dig what BIT.TRIP RUNNER brings to the table, and far be it from me to say not to like something people seem to enjoy, but the game feels masochistic for nostalgia's sake. There's no denying its style, but you'd be hard pressed to locate any real substance here. And if you choose to play BIT.TRIP RUNNER, make no mistake, you will be pressed...hard.

When it came time for me to decide what I wanted to play in my grade school band, I chose percussion. Drumming seemed more fun than brass or woodwinds, but I was also more confident in my ability to keep a beat over maintaining melody. My sister took piano lessons, which I was encouraged to take as well, but never did. We got a programmable electric piano at home eventually, and rather than actually play conventional music, I'd setup the percussion kit that assigned individual drums and cymbals to specific keys and make all sorts of noise. There was also a neat trick you could do by pressing two low-octave "square lead" keys at the same time, producing some pretty satisfying bass rumbles. I own a MPC drum machine, though it's been sorely underused. I adore Rez and was a die-hard DDR player for several years. In short, though I would not call myself a musician of any kind, I know my way around button/key-based beat making. On its surface, I should love BIT.TRIP RUNNER.

Unfortunately for me, RUNNER plays how I always feared piano lessons would go: demanding, unforgiving, and with a slavish dedication to someone else's creativity rather than my own. In RUNNER, you can't study notes on a page to prepare, you must react in real time and memorize the level's patterns through failure. At most, you have a full second to recognize what object is heading your way and tap the appropriate key to evade or deflect. Each time you screw up, it's like the piano instructor wraps your knuckles with a ruler and points to the first note on the sheet. If you play a piano piece correctly, you enjoy the satisfaction of hard-earned accomplishment along with the joy of hearing a song that you presumably like. In RUNNER, you just earn arbitrary points and the music you've produced only occasionally sounds like a song. There is no level editor or any way of really getting hands-on with the mechanics beyond the prescribed courses.

People have compared RUNNER to mobile games like Canabalt and Temple Run for their similar, forced running perspectives. Both Canabalt and Temple Run use randomized obstacles and challenge players to get farther than their previous attempt, but as far as I'm aware, neither has endpoints. RUNNER is broken up into 36 preset levels, and withholds progression until you complete the stage prior. The big difference between RUNNER and something like Canabalt is how you feel after triggering a fail state. With Canabalt it feels like the game playfully dares you to try it again. You know losing is inevitable, but it's fun to try and get farther than last time. In fact, "losing" isn't really "losing," it's just the end of the round. Retries in RUNNER are instantaneous. If you forget to kick a box on cue, the game zips you back to the start of the stage, and after a brief moment you're back on your way again. I applaud Gaijin Games for making the process so snappy, but subsequent runs feel more like a matter of survival than heartfelt attempts on the part of the player. You're trapped in the gameplay loop until you either win or cry "uncle" and quit.

There are collectable gold bars throughout RUNNER that encourage a more daring style of play, but the game doesn't offer rewards that merit the effort required to snatch them all. If you do collect every gold bar in a level you can play a bonus Pitfall-styled area, which is neat a couple times, but not 30+. You only get one try at the bonus levels per completion of a regular stage, which means you may have spent a half hour trying to get a perfect run, only for your "prize" to last a fleeting handful of seconds. The numerous retries on regular levels pushed me to ignore the gold bars as much as I could, eliminating several tricky maneuvers from my regimen, but also rendering the music more spartan, lacking the distinctive chimes emitted by grabbing the bars. You could interpret the game as an incisive metaphor for the daily, 9-5 grind perpetuated by an uncompromising capitalist economy, but that's an unearned credit. Instead, playing BIT.TRIP RUNNER feels like a really difficult motor skills exam – something for the sport stacking set.

I'm being pretty hard on RUNNER, but it does have its merits. Visually, the game renders Atari 2600 graphics as 3D cubic blocks to grinning, stylistic effect. If you collect enough point multipliers in a level, an old-school Activision rainbow will tail behind the titular runner as it goes – RUNNER's incentivization at its most effective. Mechanically, the game is as sharp as it gets. Though it asks for tight precision, failure is never the result of ambiguous design. I could knock the effectiveness of RUNNER's musical implementation, but having listened to the soundtrack outside of the game, their track selection is appropriate and catchy. Lastly, I began this review by comparing RUNNER to Bop It, but I should point out that I actually like Bop It. It's a party icebreaker game that asks players to focus their attention, likely in a social situation that requires otherwise – a humorous juxtaposition. As an unfortunate point of contrast, there just isn't much to laugh about in RUNNER.

Still, there are clearly a lot of people who dig what BIT.TRIP RUNNER brings to the table, and far be it from me to say not to like something people seem to enjoy, but the game feels masochistic for nostalgia's sake. There's no denying its style, but you'd be hard pressed to locate any real substance here. And if you choose to play BIT.TRIP RUNNER, make no mistake, you will be pressed...hard.

Monday, October 8, 2012

Review: Digital: A Love Story (Mac)

It's often taken for granted that people who play a lot of video games know a lot about technology. I'll attest that there is generally aptitude in these circles beyond that of the non-gamer crowd, but it's not something that comes entirely natural. Maybe I'm just being defensive because I was always late to the party on so many aspects of new and emerging technological trends in the past 3 decades. I didn't send an email or use AIM until I started college in 2002. Same goes for having a cell phone for more than emergency calls. I would have needed to be unrealistically aware of the personal computer scene at a very early age to feel nostalgic about the interface of the Amie Workbench, an Amiga analogue, and Bulletin Board System (BBS) communications represented in the game, Digital: A Love Story. Since I wasn't, few of the game's techie in-jokes and references stick. However, since Digital places you in a sort of 1988 simulation mode, the unfamiliarity lent itself to a more personally authentic experience.

You begin Digital as a someone who's using, for all intents and purposes, the Internet for the first time, but through the very limited lens of the Amie Workbench. Visually, the game is the computer screen: everything fits the blue/white/orange color scheme, the monitor has heavy scanlines, and the cursor is a big, fat, red arrow. You receive a message from a friend of your dad that tells you what to do to get on BBSes and chatting with folks. Where instructions in a game can often remove you from the experience, here everything is presented in proper context and actually reads like messages real people would send. Because the connection between using a computer to play and the game virtualizing a specific operating system is so direct, very little suspension of disbelief is needed to jump into the narrative.

As the title suggests, Digital is a love story, but it's also a mystery. You're introduced to the "love interest" character, *Emilia, early on, and when she disappears, it's up to you to figure out what happened. The narrative convention, which is also the primary game mechanic, is the exchange of BBS posts and private messages. Everyone you interact with has a unique voice and motivation, creating conversations that reach far beyond typical NPC fare. You never actually type any messages, instead simply hitting reply and reading contacts' responses. This string of communication works best when you're in "conversation" with one or two other people and the back and forth is readily apparent. At other times you'll just callously reply or send PMs to everyone on your list, making sure you're doing everything necessary to trigger the text that will allow you to progress further in the story. The introduction to *Emilia follows the better of those two paths, and though it's clear that I was just messaging a fictional character as part of an interactive short story, I did develop an attachment to that character; enough of an attachment to drive the mystery plot forward with a degree of urgency.

The writing in Digital is very consistent, believable, and emotionally affecting. Digital's designer and author, Christine Love, bills herself as a writer first, and it shows. That's meant as a compliment to her writing skills, not a knock on her game design abilities. Truly well written games are few and far between, but even fewer are as dependent on quality writing as Digital. Characters' messages vary in articulation and sophistication, as you'd expect from a bunch of random people on the Internet. I'm reminded of Gus Van Sant's teenager-starring Paranoid Park for how real its characters felt despite, or perhaps because of, the amateur statuses of its actors. Love is likewise able to find a tone that is reflective of the production process, and somehow more authentic in doing so.

Digital plops you into the world of BBSes, stranger-in-a-strange-land style. Yes, there's a missing person mystery to solve, but navigating the uncharted online world is a mysterious voyage in its own right. Imagine a game that has a clear story objective, but in order to proceed you need to drive a tractor, and before you can drive the it you have to figure out how it works. Do you need keys to start it? Where are the keys? Which lever is for reverse? Oh wait, does this run on gas?! BBSes are just as foreign to me as tractors, and I appreciated how Digital didn't assume any prior knowledge. If there's a tendency nowadays to forget just how open the Internet is, typing in phone numbers in hopes of connecting to a heretofore unseen places is a healthy reminder. No one even dials numbers to place phone calls anymore, further distancing us from the real technological processes happening in the background. If you did hand-dial phone numbers, you might mess up and call a random bystander by mistake. In Digital, instead of hanging up and correcting the error, every number has an unknown on the other end; there's a sense of discovery.

The feeling of openness makes for an ideal learning space, which goes as much for the in-game world as the one outside of it. Digital teaches you about BBSes and early Internet history through message texts, but in allowing you to actually dial the numbers and direct message other users, you learn by doing. The mystery/love story paces you through the learning process, heightening the meaning behind your actions. Later on, the Internet "history lesson" takes some sensationalist turns, but it makes for a great moment of culmination when you finally gain access to the fabled University BBS where they don't just have direct messages, they have email! A story that's willing to go a little over the top is helpful to make up for the potential dryness of a game centered around an archaic computer interface. The online communications depicted in Digital remain the foundation that our modern Internet is built upon, reminding us of the vast expanses available to users at increasing speeds and densities. It's up to us to make the stories real.

Digital: A Love Story is available to download for free here.

You begin Digital as a someone who's using, for all intents and purposes, the Internet for the first time, but through the very limited lens of the Amie Workbench. Visually, the game is the computer screen: everything fits the blue/white/orange color scheme, the monitor has heavy scanlines, and the cursor is a big, fat, red arrow. You receive a message from a friend of your dad that tells you what to do to get on BBSes and chatting with folks. Where instructions in a game can often remove you from the experience, here everything is presented in proper context and actually reads like messages real people would send. Because the connection between using a computer to play and the game virtualizing a specific operating system is so direct, very little suspension of disbelief is needed to jump into the narrative.

As the title suggests, Digital is a love story, but it's also a mystery. You're introduced to the "love interest" character, *Emilia, early on, and when she disappears, it's up to you to figure out what happened. The narrative convention, which is also the primary game mechanic, is the exchange of BBS posts and private messages. Everyone you interact with has a unique voice and motivation, creating conversations that reach far beyond typical NPC fare. You never actually type any messages, instead simply hitting reply and reading contacts' responses. This string of communication works best when you're in "conversation" with one or two other people and the back and forth is readily apparent. At other times you'll just callously reply or send PMs to everyone on your list, making sure you're doing everything necessary to trigger the text that will allow you to progress further in the story. The introduction to *Emilia follows the better of those two paths, and though it's clear that I was just messaging a fictional character as part of an interactive short story, I did develop an attachment to that character; enough of an attachment to drive the mystery plot forward with a degree of urgency.

The writing in Digital is very consistent, believable, and emotionally affecting. Digital's designer and author, Christine Love, bills herself as a writer first, and it shows. That's meant as a compliment to her writing skills, not a knock on her game design abilities. Truly well written games are few and far between, but even fewer are as dependent on quality writing as Digital. Characters' messages vary in articulation and sophistication, as you'd expect from a bunch of random people on the Internet. I'm reminded of Gus Van Sant's teenager-starring Paranoid Park for how real its characters felt despite, or perhaps because of, the amateur statuses of its actors. Love is likewise able to find a tone that is reflective of the production process, and somehow more authentic in doing so.

Digital plops you into the world of BBSes, stranger-in-a-strange-land style. Yes, there's a missing person mystery to solve, but navigating the uncharted online world is a mysterious voyage in its own right. Imagine a game that has a clear story objective, but in order to proceed you need to drive a tractor, and before you can drive the it you have to figure out how it works. Do you need keys to start it? Where are the keys? Which lever is for reverse? Oh wait, does this run on gas?! BBSes are just as foreign to me as tractors, and I appreciated how Digital didn't assume any prior knowledge. If there's a tendency nowadays to forget just how open the Internet is, typing in phone numbers in hopes of connecting to a heretofore unseen places is a healthy reminder. No one even dials numbers to place phone calls anymore, further distancing us from the real technological processes happening in the background. If you did hand-dial phone numbers, you might mess up and call a random bystander by mistake. In Digital, instead of hanging up and correcting the error, every number has an unknown on the other end; there's a sense of discovery.

The feeling of openness makes for an ideal learning space, which goes as much for the in-game world as the one outside of it. Digital teaches you about BBSes and early Internet history through message texts, but in allowing you to actually dial the numbers and direct message other users, you learn by doing. The mystery/love story paces you through the learning process, heightening the meaning behind your actions. Later on, the Internet "history lesson" takes some sensationalist turns, but it makes for a great moment of culmination when you finally gain access to the fabled University BBS where they don't just have direct messages, they have email! A story that's willing to go a little over the top is helpful to make up for the potential dryness of a game centered around an archaic computer interface. The online communications depicted in Digital remain the foundation that our modern Internet is built upon, reminding us of the vast expanses available to users at increasing speeds and densities. It's up to us to make the stories real.

Digital: A Love Story is available to download for free here.

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Review: Limbo (Mac)

The most common understanding of afterlife pit-stop, Limbo, is one that blends in with Purgatory, both associated with wavering, in-between states. In 2007 the Catholic Church released a document stating their thoughts on the eternal fates of infants who die without being baptized, concurrently addressing the validity of Limbo. Even though their proclamation did not directly disqualify the existence of Limbo, they didn't take credit for the idea either. Officially speaking, Limbo is only perpetuated by individuals, not the church, and was (and still is) more recognizable through the lens of pop culture than religious mandate. While the 2007 document put the malleability of church doctrine into sharp relief, Danish video game developer, Playdead, was already hard at work on their debut title, Limbo: a game centered around the titular mystical locale.

Much the same way that the Catholic Church has decided to allow its members to believe in Limbo if they so choose, Playdead's Limbo (released in 2010) doesn't tell you what to believe about its world. The developer has left scant details as to what is really happening in the game aside from the premise that a boy (the playable character) is looking for his sister. The setting begins in a woodland area, transitions into an urbanized setting, and ends in a cavernous factory where gravity itself is in flux. Does the boy find his sister in the end? Maybe?? Even that is debatable. Some narratives encourage participants to fill in the gaps with their mind. Limbo is more like a figurative painting: you know what you're looking at, but it's up to you to decipher meaning enough to make the piece matter.