Showing posts with label crypt worlds. Show all posts

Showing posts with label crypt worlds. Show all posts

Monday, September 16, 2013

Development Hell: Crypt Worlds (Mac) Review

The struggle between order and chaos is a recurring theme in video games. Most often this dynamic is implemented as part of a game's narrative where good (order) clashes with evil (chaos). Players are typically thrust into the role of the hero, bent on restoring order to the world using the game mechanics at their disposal. These mechanics themselves function within ordered systems that reinforce behaviors and build expectations. Chaos is randomness and unstructured play, which are represented in games as obstacles and extra game modes respectively. If ever there was a game that straddled the line between order and chaos, it's Crypt Worlds: Your Darkest Desires, Come True!.

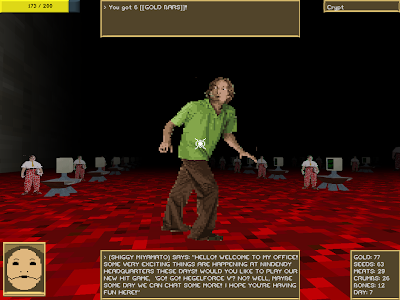

The conflict between order and chaos is at the center of Crypt Worlds' systemic conceits, its narrative focus, and even its meta-narrative commentary. Through the game's multiple endings, you're literally afforded the choice between restoring order or unleashing chaos. At first blush, Crypt Worlds is an indecipherably weird game; it's got the dark, pixelated tunnels of King's Field, the routine collecting and planting of Farmville, and the twisted irreverence of Noby Noby Boy. In town, buckle-hatted villagers trudge through their work and complain about "sky pilgrims." In underground corridors, skull-faced consumer hordes crave "burgs." You're main objective is to stop the bloody-eyed elephant thing Dendygar from taking over the world. You have 50 days to find and collect stuff and you can pee on everything. Go!

By that description, Crypt Worlds might seem pretty chaotic, and for the initial hour or so of gameplay, it is. There are so many random weirdos to talk to and systems to comprehend that it feels like swimming blindfolded. The game does give you a couple hints to get you going, but not much beyond "try leaving the house." You can pick up seeds, which are scattered around the land, and you can search trash cans for other plantable items and gold. Acquiring items fills up your reserve of urine, which can be *ahem* relieved, much to the annoyance and disgust of the populace. If you speak to everyone, pick up every item, and indeed pee on everything, eventually you'll begin to piece together how Crypt Worlds' various systems and currencies intertwine.

However, it's not as simple as all that, as Crypt Worlds throws its fair share of curveballs to keep you unsettled. Occasionally and seemingly at random, when you click on a character sprite to speak with them, they will burst into a disintegrated "error" pattern of red and yellow pixels, and will not reset until the next day. In the titular crypt area, I was thrown through the ceiling by an unknown force on multiple occasions and found myself on top of the level architecture. Is this a real bug, a simulated glitch, or some broken code left in the game to make me think it was created on purpose, just to mess with me? I don't know, but all you can do at that point is jump off the edge and into the abyss, only to land in a pit of game development nerds below. Turns out the nerds slaving away in the cavernous sweatshop are working on a game also called Crypt Worlds; perhaps it's the very game you're playing. That would explain the "bugs."

Mechanically, Crypt Worlds is a game about collecting stuff, but the trick is knowing how to maximize your collecting potential. Simply searching around the environment yields limited results, so you'll need to begin trading, planting, and peeing to exploit the game's economy to the fullest. At some point, I ran out of things to do while waiting for a new archaeological digs to open (yeah, that's a thing), but I didn't have enough money to buy the things I needed. The best way to hunt up currency is by searching trash cans every day, and the more you can do to increase the number of trash cans on your daily route, the richer you'll be. I reached a point in Crypt Worlds where for several in-game days I would do nothing but wake up, root through garbage all over town, and then go back to sleep. I felt like a dumpster diver looking for recyclable materials, which is something I've never felt in a game before. What begins as playful poking around eventually shifts to an ordered if not downright mundane process of scrounging for coin. I began to save urine for specific places where it furthered my progress too. For instance, if you pee on the detective, he'll drop gold bars, and peeing on bones after planting them will yield greater returns come harvest. It's screwy logic, but logic nonetheless.

Crypt Worlds has multiple endings depending on which special objects you've collected. Recover Goddess Moronia's relics and return them to her to face off against Dendygar or collect hidden crystals and take them to the Hellzone to summon the Chaos God. In my first playthrough, I went the chaos route, but unintentionally so. Maybe I wasn't paying close enough attention, but I had no idea that jumping down the literal hell hole with all of the crystals would trigger the irreversible series of events that follows. In retrospect, whether it was "good" or "bad," waking the Chaos God by accident definitely felt like the "right" ending. It was the game's way of throwing my arrogance back at me. "You think you've got this all figured out? Well, surprise!" With no saves states to reload, it's back to the beginning if you want to try for a different ending.

Crypt Worlds doesn't side with either order or chaos; it presents itself, and video games in general, as a battleground for the conflict. We "play" games, but that's different than being "at play." The disparity is partly that games tell you how to play instead of determining those constraints for yourself. In this way, game design itself can fit more in the realm of play than the actual experience of the game –a stance both reinforced and contested by the inclusion of the nerdy game making drones in Crypt Worlds' shadowy developer pit. The most out-there, freeform game design concepts are eventually called to order by demands of wieldable mechanical systems, and no matter how organized and polished your systems may be, they're still prone to be overturned by chaotic elements. This is the essence of Crypt Worlds, which truly is, in game development terms, your darkest desires, come true.

Monday, August 12, 2013

Blips: The Ludonarrative Dumpster

Source: Ludonarrative dissonance doesn't exist because it isn't dissonant and no one cares anyway.

Author: Robert Yang

Site: Radiator Blog

I'd highly suggest giving Robert Yang's new blog post discounting the relevance of the term "ludonarrative dissonance" a read. I provided a link above, fancy that. It's an at-times hilarious description of the dissonant nature of Bioshock Infinite that few who reviewed the game seemed to care about. Yang goes on to argue that critics and players at large don't seem bothered by ludonarrative dissonance at all anyway. We've adopted processes where we recognize "gameisms" (borrowing a term from Tom Bissell) as exceptions to the rules that would otherwise be labelled "dissonant."

One example Yang offers in Bioshock Infinite that stood out for me was the game's supposed commentary on the concept of poverty, yet as the protagonist you find money in trash cans all over the place. Now, I haven't played Infinite, so I can't comment directly on the game's execution here, but it's very effective at illustrating Yang's point. I'll be writing about the game Crypt Worlds soon, which tackles the subject of currency, including finding money in garbage bins, in an extremely thought-provoking way. In short, dumpster diving for cash isn't something most people do, but many video games make it seem normal. Crypt Worlds made me step back and consider that I was spending multiple "days" in in-game time exclusively making the rounds through town, searching garbage cans for money. I really felt like I was a scrounger in what is, in every way, a messed up place. Crypt Worlds didn't tell me it was thematically about poverty or financial systems (among other things), I perceived that through playing it.

And I think that's also part of the issue here. Games, particularly big-budget games with significant PR pushes, build up hype and preconceptions that are meant to sell the game, and these statements are given credence when it comes to critique. The "authorial intent" ingrains itself over time, even before the game is released. Games don't say, "this is about poverty," they say something about poverty, usually about the how it's unjust, conveyed by building empathetic relationships with impoverished characters. However, marketing says "this game is about poverty" in hopes that critics and players will look for it in the game. Again, I haven't played Bioshock Infinite, but I could rattle off half a dozen themes that the game supposedly wrestles with that will be impossible to unknow when/if I decide to play it someday.

I agree with Zolani Stewart's reaction in the comments that the division between "game" and "story" parts is wholly arbitrary and falsely frames critical discussion, and that the problem isn't that games need to rid themselves of dissonance or that dissonance in and of itself is enough to warrant damning critique, but if a game is, through whatever procedural means, presenting a thematic opinion that is undercut by other elements of the game, it's worth pointing out. By the sound of it, according to Yang, Bioshock Infinite undercuts itself constantly. If no one seems to notice, is it because dissonance doesn't matter or just that games and game media are proficient at drawing most players' attentions away from such discrepancies?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)