Monday, September 30, 2013

Blips: Actions into Words

Source: Verbs

Author: Mitch Krpata

Site: Insult Swordfighting

What do you do in a video game? No, like what do you do? When trying to come up with a basic description of a game, it's helpful to frame it as a series of verbs. For a game like Space Invaders, there aren't very many: aim shoot, dodge. Things get more complicated in games that begin to add contextual modifiers to those verbs, which you can think of as adverbs. In the Street Fighter series you can kick your opponent, but there are different buttons for different kinds of kicks, further modified by whether your character is in the air, standing, or crouching. Mechanically speaking though, you're still just kicking.

These verbs are commonly referred to in game design as "mechanics," but I appreciated Mitch Krpata's use of the word "verbs" to describe them because it gets at a more plain-spoken understanding of what options a particular game provides. In his piece, Krpata laments the lack of evolution in the verbs of the Grand Theft Auto series over the years, and the limited verbs of Bioshock Infinite in comparison to Dishonored. Having mechanical variety can offer more agency to the player, allowing them to approach situations in ways they see fit.

While I definitely see where Krpata is coming from, part of me sees this as a matter of personal preference. Krpata himself says that there's nothing inherently wrong with a game like Bioshock Infinite focusing on shooting instead of anything else, it just frames the protagonist's role in the game world under limited terms. Games with few verbs tend to focus on perfecting mechanical execution of those actions over time, but can also be implemented in gameplay that isn't "skill-based." In Proteus, your verbs are walk, look, and sit. There's no way to "get better" at these things, but simply doing them is pleasurable and entertaining. Proteus doesn't need to be a sandbox of mechanics to be interesting because the island you explore is what's interesting, not so much your "character."

Games use verbs to place you in an empathetic mindset with the protagonist. I haven't played Bioshock Infinite, but I suspect the issue might be that the game's world and narrative express a depth that is hamstrung by your limited mechanics. In Proteus, this isn't a problem because the low mechanical focus puts the emphasis on the island instead, which does all sorts of things that would go unnoticed if you were busy playing around with a list of verbs. I hope this illustrates that mechanical diversity should be taken on a case-by-case basis, and that the verbs that make one game great, could very easily ruin another one.

Friday, September 27, 2013

Blips: Fall Fling

Source: Untold Riches: An Analysis Of Portal's Level Design

Author: Hamish Todd

Site: Rock, Paper, Shotgun

Portal's a pretty smartly designed game. I played it for the first time a few months ago, and was impressed by inventive physics-based puzzles. Portal has proven to be a tremendously influential game in terms of environmental storytelling and making your standard block-pushing minigame even more boring that it already was. There's just something kind of amazing about staring into a portal you've created and seeing an entire area, just waiting to be stepped into. It has a similar appeal to mirrored surfaces in games; offering moments where you can see your character and the world around you from a different perspective than the one offered by the game's camera.

Now, the article by Hamish Todd that I wanted to share is all about Portal's physics –specifically the "fling" technique. The picture above illustrates what flinging is all about. Basically, you set up a situation where you jump from a height through a portal on the ground, only to emerge from a wall portal with he forward momentum gained from your quick descent. The result is that you are flung forward through space. The fling ends up becoming one of Portal's core conceits, sometimes asking that you rotate or shoot a new portal in midair to change trajectory. It seems so simple, yet it hadn't really been done before –not like this anyway.

In his article, Todd walks through a number of different puzzle rooms from Portal and some of the extended challenges, showing how many different ways the fling was implemented (some great illustrative GIFs in there too). The fling was a naturally occurring phenomenon in the game engine before it became central to Portal's gameplay, as if it was something to be discovered. This reminds me of how Devil May Cry's air juggling mechanic was born out of an Onimusha glitch where enemies weren't falling to the ground after being launched above you. It's a philosophy of looking at something that happens unexpectedly and embracing it for what it is. How refreshing.

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Blips: Midwestern State of Mind

Source: Chicago: Home of a New Indie Gaming Renaissance

Author: Jordan Minor

Site: Kotaku

It's no secret the the vast expanse of land between the two coasts of the United States is largely neglected when it comes to cultural video game happenings. There's an east coast epicenter up in New England and a west coast expanse between San Francisco and Los Angeles. Except for Austin, Texas, there's not a lot of video game scene visibility in the country's midsection. However, if a recent article by Jordan Minor for Kotaku is to be believed, Chicago may be on its way to filling that void.

Minor's piece offers up a solid list of names and projects that are gaining more national recognition, and I find the whole thing inspiring. As a St. Louisan it can be alienating to be invested in a cultural medium like video games, but feel limited in what physical membership in such a community means. If I wanted to attend just about any major gaming convention, it would have required a pilgrimage-level of effort to get there. Perhaps sometime in the near future, that won't feel like the case anymore.

Of course, I live in New York now, so I'm able to see the industry from the other side of the lens, but I don't plan to stay here forever, and if I find my way back to the Midwest, Chicago seems a likely destination. So, maybe my motivation is a bit self-serving, but I also think the industry could use more perspective from folks who aren't around the corner from Silicon Valley, Hollywood, or Times Square, even on the indie front. So, all I really have to say is, keep it up, Chicago!

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

Gotcha!: An ARG Story

My investment in this whole horse_ebooks thing was pretty low to begin with. An infamous Twitter bot that spits out spam poetry (that's a freebie, Def Jam) wasn't actually fully automated this whole time. Or maybe it was and was just being carefully curated by a couple humans; the details are fuzzy. Turns out both horse_ebooks and the Pronunciation Book YouTube channel were both being run by Jacob Ballika and Thomas Bender, and the string of cryptic clues emitted recently by both were the lead-up to a browser-based FMV game called Bear Sterns Bravo. As a result, both the Twitter handle and YouTube account will cease further updates.

Oh well.

Perhaps the most important aspect of this whole string of events is the framing of Ballika and Bender's initiatives as art, even staging a gallery show called Bravospam, complete with live performances. You can call (213) 444-0102 and hear Ballika or someone else speak a horse_ebook-ish-ism into a phone. There are a few videos on display too featuring characters from Bear Stearns Bravo staring back at you, as if "waiting to be spoken to," according to the in-gallery text explanation. Additionally, horse_ebooks and Pronunciation Book are referred to as online "installations."

The common thread that supposedly ties the whole thing together was the alternate reality game (ARG) that led up to this grand reveal. Cryptic clues were dropped around the Internet and people read into the patterns of spam being emitted by horse_ebooks looking for clues. The people who pursue hunts like this are intrigued by the mystery, curious to find out what's at the end of the rainbow. In this case, as is the case with just about every other ARG, the pot of gold is an advertizement for an upcoming product. At best these reveals are predictable and don't unfairly inflate players' expectations. Such was the case with the Boards of Canada ARG earlier this year, which everyone knew was being staged by the band and ended in the reveal of a new album, which while not a revolutionary announcement, was something that the ARG players were interested in and kind of saw coming. At worst the ARG culminates in a marketing ploy for something largely disconnected from the game everyone was playing and the point of original interest. Enter Bear Stearns Bravo.

This is a problem for the gallery show as well, which doesn't forge much of a connection between Ballika and Bender's suite of Internet memes and their FMV game about financial regulation, to say nothing of either component's individual value. It hitches onto the label of "art" hoping it will solve this problem and act as the rescue copter, lifting them out of the enraged jungle of followers and subscribers who feel lied to. It doesn't fare all that well as an art show though. Even the title of the exhibition, Bravospam, comes off as a lazy portmanteau of the two distinct concepts. There's no rulebook that states a body of artwork can't have a bifurcated concept, but in the case of Bravospam, it's more of a bait and switch.

And maybe that's the point.

I've played Bear Stearns Bravo, and it's a pretty funny game. If Tim & Eric made an FMV game about the housing crisis of 2007 it would probably look something like this. You play Franco, a government regulator, charged with investigating and taking down financial firm Bear Stearns for their credit default swap practices, among other white collar deceptions. The aesthetic of the game is straight out of the late 80s and early 90s, when FMV games were popular. Everything is shot and rendered in high definition though, unlike the muddly pixels and low resolutions of those old games. Actors ham it up for the camera and knowingly diverge into goofy, nonsensical tangents about their personal lives. Your only control in the game is selecting from dialogue options when questioned. The whole thing takes less than an hour.

The best thing to come out of Bravospam is the all-too-short scene in Bear Stearns Bravo where you encounter Champion and Dynasty, two sleazy, fast-talking debt slingers. They toss glowsticks (mortgages) back and forth and yell into disconnected phones, while justifying their behavior as essential to keeping the worlds systems in motion. It's a great parody of the egos that created the housing bubble and their tenuous relationship with credibility. At one point, you can try and empathize with them by saying that regulators and bankers aren't all that different, but they quickly dismiss your remark and continue shouting into their phones, totally self-absorbed.

The horse-ebooks/Pronunciation Book ARG isn't wholly unlike Champion and Dynasty, both are convincing you to invest in something that appears one way, but yields an unexpected return. And like the real world investment banks that facilitated the global financial crisis, Ballika and Bender have opted for the crash and the spectacle. I understand wanting to move on from silly web jokes that require daily iteration. I wouldn't hold it against Dan Walsh if he stopped doing Garfield Minus Garfield and said, "OK, I'm doing this other thing instead." Surely the appsurfing generation, with their supposed short attention spans, would be able to empathize with the horrors of boredom. This, the same generation that brought us the term "catfishing," too. The goodwill from players was there, but it was exploited instead of shepherded to the next thing.

A second episode of Bear Sterns Bravo is available for $7 from the game's website. It's probably good too, but I have a hard time seeing horse_ebooks fans giving Ballika and Bender any money considering they made a name for themselves through misdirection, and I'm not sure anyone else cares enough to pay attention.

:reposted on Medium Difficulty:

Tuesday, September 24, 2013

Blips: Target Practice

Source: The problem with guns

Author: Zolani Stewart

Site: The Fengxi Box

I'm really digging this post by Zolani Stewart which is the first in a series about guns in video games. I particularly endorse the use of the word "targetry" to label the action and contextual implications of gun mechanics. Targetry is a great word here because it goes beyond just shooting, and gets at the core conceit of games that present the player with a gun in the lower third of the screen by default. In most first-person games of this sort, you can't even lower your sights to speak with people; you are always aiming and everyone is always being targeted. Third person games are more conscious of this, but only marginally so.

As Stewart details, targetry seems to derail everything interesting it comes into contact with. Maybe I did have a very thought-provoking conversation with a support character, but I can't get over the fact that that character was basically speaking to me at gunpoint, and how they didn't seem phased by the smoking barrel in their face. Maybe the game doesn't care about that though and is content to just be a quickly forgotten time-filler, which is fair enough, but doesn't make for much of a cultural object worth critiquing or archiving for future reference.

Worse still "Big Budget games that are rooted in targetry end up perpetuating simplistic perspectives on complicated issues, perspectives that can even be harmful: the uncritical use of torture scenes, apolitical racism, shallow critiques of American culture and bottomless cynicism," as Stewart puts it.

But guns in games aren't inherently a bad thing, as Stewart points out; they're just missing the drama. This is the drama that can give gun violence the gravitas to be taken seriously. Having recently played The Walking Dead, I've seen that there are ways to include guns and even targetry in games in ways that ground those action with emotional weight. That I'm saying this about a zombie game (a genre that revolves heavily around headshots) should be inspirational. If a zombie game can do it, then there are probably ways to maximize the power and impact of guns in just about any other type of game. It's not that every game should aspire to be the same sort of experience, but if a game is primarily trading in targetry, then whatever else it has to say will likely go unheard.

I'm looking forward to part two of this series which will look at SuperHot, which Stewart claims "gets guns right." Should be good. Til then...

Monday, September 23, 2013

Blips: Arco, My Arco

Source: Real Simulation, False Prophecy

Author: Dan Solberg

Site: PopMatters

My piece on SimCity 2000 and the heartbreaking lack of real-world arcologies finally went live on PopMatters today. I'm pretty happy with it, though they didn't use my screenshot (above) that I took for them. I was playing quite a bit of SimCity 2000 at the time, but that was back in June, and I haven't gone back to my city of Teasureton too much since getting into full-on arcology production. Sure, I finished a large scale highway project and built an entire subway system, but that game is at its best when you're expanding. As neat as an arcology is, reformatting your city to be homogeneously covered in the same 4 sprite models is a pretty dull activity, and sucks the personality out of your city.

That said, I'd love to go back in at some point and start over from scratch, maybe in a mountainous terrain. I've never successfully gotten a missile silo installed in one of my cities, so that's something to shoot for. Anyway, I hope you enjoy the PopMatters piece –maybe it won't be the last time I show up there...

Friday, September 20, 2013

Blips: Papers, Please

Source: Crowdfunding's Secret Enemy Is PayPal

Author: Patrick Klepek

Site: Giant Bomb

In case you hadn't noticed, there's a lot of money being thrown around in crowdfunding campaigns these days. PayPal, the online payment processing company has noticed as well, since they're handling a significant portion of the funds being contributed to these campaigns. More than a handful of times, PayPal has withheld funds and frozen accounts of some high-earning projects as a means of making sure the companies' intentions are legitimate and defending PayPal from getting stuck footing massive chargeback bills. The problem is that these game developers aren't properly informed of this procedure, and have had to resort to public complaints to reverse PayPal's actions. In a new article by Patrick Klepek, he details the frustration that crowdfunded game developers are facing when they're raised a bunch of money, and then aren't given it without having to spend time and energy making a fuss.

From PayPal's side, the desire to protect themselves from the repercussions of scammers and money laundering schemes is legitimate. The problem is how they're going about it. If it was stated up front that there would be a set timetable for the release of funds from PayPal, that would be one thing, but is the instances that Klepek notes in his piece, PayPal typically doesn't make their move until after a campaign has come to a close. Even a word from the crowdfunding platforms would be a helpful forewarning about the series of events to follow. Perhaps PayPal could offer a verification system upfront, the same way they do after the fact for establishing legitimacy, so that these game developers can clear up any confusion before it becomes an issue.

That said, Kickstarter and IndieGoGo are services that allow users to raise money on nothing but promises, and don't necessarily require any prior experience or background in what's being projected (though it certainly helps). Still, it's hard to see these recent kerfuffles as anything but poor communication and customer policy on the part of PayPal, which is already just about the least human, most faceless company I can think of. I'm glad to hear that so many of these cases did see resolution in the end, and hope PayPal has learned their lesson here. If they're not working on changes to keep unnecessary funds withholding regarding crowdfunding campaigns from occurring on a regular basis, then their reputation will see further damage and the doorway for competition will crack open a little further. Ultimately, that might not be such a bad thing either.

Thursday, September 19, 2013

Blips: RIP Hiroshi Yamauchi, 1927-2013

Source: Hiroshi Yamauchi, the executive who turned Nintendo into a video game giant, dies at 85

Author: John Teti

Site: The Gameological Society

I don't have a whole bunch to add to what's been said already, but I wanted to link to an obituary for former Nintendo executive Hiroshi Yamauchi, who passed away this week at the age of 85. It's astounding to consider how long Yamauchi was running things at Nintendo –over 50 years before stepping down in 2002. Though Shigeru Miyamoto was the man behind the design of iconic characters like Mario and Link, Yamauchi was running things back when Nintendo's primary business was playing cards. While many Japanese companies have their hands in a diverse array of industries, that Nintendo was still a games company at its inception is pretty cool.

Of course, Yamauchi's Nintendo would go on to be a video game powerhouse, reigniting the industry after the collapse of Atari and mounting skepticism around the medium as a reliable investment at retail. Yamauchi's Nintendo is the one I have a personal affinity for as well. The NES was my first home console, and even though I diverted to Sega in the 16-bit era, I came back for the Nintendo 64 years later. Those systems are a part of my identity now, and though I know massive commercial efforts like video game console production are a team effort, Yamauchi was in the driver's seat. So, I feel like I owe him a debt of gratitude. Who knows where video games would be without him?

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Blips: Framing Devices

Author: Jonas Linderoth

Site: YouTube

I stumbled across this video presentation the other day by University of Gothenburg professor Jonas Linderoth on why it feels like games have a difficult time tackling serious subject matter. He explains that the way an object is framed in a game is always a layer removed and abstracted from what we understand that object to be outside of the game. The example he gives is one where kids are playing a game with an old shoe he had provided them, using the shoe as a kind of "ball" where it was important to have possession of it. In the game, his shoe had taken on a totally different significance that what it had before, and in turn, also lost a lot of other context. The kids don't know Linderoth's personal history with the shoe, and the stories that could be told of where it had been and how it fits on his foot. Instead, the shoe has taken on a ludic meaning that sees it as a prized possession and a means to winning the game.

Now, the kicker is to substitute the shoe in the kids game with objects that carry broad historical and cultural weight; Linderoth settles on a Nazi flag as an example. Casting an object that represents thoughts and actions that most people find reprehensible in the role of an important and, in the game context, sacred item is likely to shock and offend. Linderoth explains that the reframing of an object in the game world inherently trivializes it, and it's up to game designers to provide proper framing to convey the meaning they're going for while also recognizing the limits of virtual representation. While I think Linderoths use of the phrase "getting away with it" pessimistically assumes designers are out to slip one past the censors, his given paths to healthy solutions are nonetheless valid.

One of those solutions is satire, which has been popping up quite a bit as it relates to Grand Theft Auto V. What happens when segments of players don't buy into the explanation they've been given as to why they should be OK with the ludic meanings attached to certain game objects? What happens when someone calls BS on your game as satirical commentary? I suppose what happens is there's a certain level of backlash, but in the case of GTA5, the overwhelming wave of critical praise, consumer buy-in, and in-game expanse swallows up the push-back. Perhaps that will change as we get further and further away from the buzz of GTA5's launch, but it also feels like the impact has already happened and the damage done.

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Blips: The Age of Games is Upon Us

Source(s): Manifesto: The 21st Century Will Be Defined By Games

Notes on Eric Zimmerman's "Manifesto for a Ludic Century"

The Uncomfortable Politics of the "Ludic Century"

Author(s): Eric Zimmerman & Heather Chaplin, David Kanaga, Abe Stein

Site(s): Kotaku, Wombflash Forest, Kill Screen

Last week, game designer and academic Eric Zimmerman published "Manifesto for a Ludic Century" and made the case for why games and game thinking will define the next hundred years. Being a manifesto, he lays out a handful of bold points such as "Digital technology has given games new relevance," "There is a need to be playful," and "Games are a literacy." These points are each followed by a couple sentences of further explanation. As part of the piece being posted on Kotaku, author and professor Heather Chaplin provides some reflection and critique of the words that immediately precede her own. It may seem strange that something dubbed a manifesto would require further backstory and something outside of itself to provide proper context, but seeing as the manifesto is meant to be but a part of a new book by Zimmerman, the extra supportive material is helpful.

In the wake of the manifesto's posting, a flurry of responses has surfaced, covering a wide range of territory. Kotaku even pre-baked a few responses from industry luminaries and extracted soundbites for a separate response article. I wanted to focus mainly on two critiques though, one by sound art/game music composer David Kanaga and one by sports media researcher Abe Stein.

In Stein's piece, he wonders who will actually take part in the ludic century, and who will watch from the sidelines. The argument is about access, which all broad, technology-based initiatives must address. For whom are digital technologies like video games and the Internet fostering a surging interest in design thinking? Stein speculates that these are privileges afforded to the minority of the world population that has access to this technology. Zimmerman even admits that his manifesto is a bit serf-serving, both proclaiming the importance of thinking like a game designer and promoting his upcoming book, which, demographically speaking, sounds a bit like preaching to the choir as well. After all, people who don't play video games and who don't have computers or smartphones won't be reading articles about them on Kotaku either.

David Kanaga's criticism is an expansive, philosophically grounded, point-by-point evaluation of the manifesto's statements. There are a lot of pools of interest here (and plenty that was over my head), but I found a through-line in his criticism of Zimmerman's framing of "play." Zimmerman speaks of playing games as a part human nature, the same as telling stories, making music, and creating images. Kanaga posits that "telling," "making," and "creating" are all forms of play as well, and that any activity can be seen as a game. Speaking of "games" specifically he says early on that "games are both playful-irrational things and highly structural things, and integrating the reality of these apparently contradictory tendencies is maybe the most important/baffling work there is to do-- in design, theory, and play. Right now, the rational aspect of games is WAY over-represented." That rational aspect is tied up in "systems thinking," which while certainly useful, can be overemphasized at the expense of play.

In the end, I'm not sure the manifesto format was the best way for Zimmerman to go, since many criticisms can be explained away by the adherence to that form (a criticism Zimmerman has acknowledged). The ludic century manifesto comes from a standpoint of assumed common ground, which is helpful when trying to convey ideas that, for many people, will be totally new ways of thinking about the integration of games and culture. However, Zimmerman chose a format that requires broad strokes, bold declarations, and positive vision, not nuance. You probably won't have a successful call to action if you can't sell people on it, so that's what the manifesto attempts to do. I wonder if Zimmerman sees the cascade of responses to his manifesto, both positive and negative, as part of design thinking in practice. Will we see a second iteration of the manifesto that incorporates this feedback? I hope so, though if anyone refers to this first go round as an "open beta," I might hurl.

:image credit GeneralPoison:

Monday, September 16, 2013

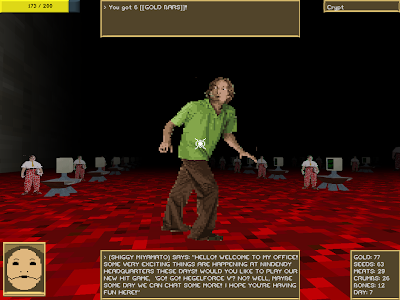

Development Hell: Crypt Worlds (Mac) Review

The struggle between order and chaos is a recurring theme in video games. Most often this dynamic is implemented as part of a game's narrative where good (order) clashes with evil (chaos). Players are typically thrust into the role of the hero, bent on restoring order to the world using the game mechanics at their disposal. These mechanics themselves function within ordered systems that reinforce behaviors and build expectations. Chaos is randomness and unstructured play, which are represented in games as obstacles and extra game modes respectively. If ever there was a game that straddled the line between order and chaos, it's Crypt Worlds: Your Darkest Desires, Come True!.

The conflict between order and chaos is at the center of Crypt Worlds' systemic conceits, its narrative focus, and even its meta-narrative commentary. Through the game's multiple endings, you're literally afforded the choice between restoring order or unleashing chaos. At first blush, Crypt Worlds is an indecipherably weird game; it's got the dark, pixelated tunnels of King's Field, the routine collecting and planting of Farmville, and the twisted irreverence of Noby Noby Boy. In town, buckle-hatted villagers trudge through their work and complain about "sky pilgrims." In underground corridors, skull-faced consumer hordes crave "burgs." You're main objective is to stop the bloody-eyed elephant thing Dendygar from taking over the world. You have 50 days to find and collect stuff and you can pee on everything. Go!

By that description, Crypt Worlds might seem pretty chaotic, and for the initial hour or so of gameplay, it is. There are so many random weirdos to talk to and systems to comprehend that it feels like swimming blindfolded. The game does give you a couple hints to get you going, but not much beyond "try leaving the house." You can pick up seeds, which are scattered around the land, and you can search trash cans for other plantable items and gold. Acquiring items fills up your reserve of urine, which can be *ahem* relieved, much to the annoyance and disgust of the populace. If you speak to everyone, pick up every item, and indeed pee on everything, eventually you'll begin to piece together how Crypt Worlds' various systems and currencies intertwine.

However, it's not as simple as all that, as Crypt Worlds throws its fair share of curveballs to keep you unsettled. Occasionally and seemingly at random, when you click on a character sprite to speak with them, they will burst into a disintegrated "error" pattern of red and yellow pixels, and will not reset until the next day. In the titular crypt area, I was thrown through the ceiling by an unknown force on multiple occasions and found myself on top of the level architecture. Is this a real bug, a simulated glitch, or some broken code left in the game to make me think it was created on purpose, just to mess with me? I don't know, but all you can do at that point is jump off the edge and into the abyss, only to land in a pit of game development nerds below. Turns out the nerds slaving away in the cavernous sweatshop are working on a game also called Crypt Worlds; perhaps it's the very game you're playing. That would explain the "bugs."

Mechanically, Crypt Worlds is a game about collecting stuff, but the trick is knowing how to maximize your collecting potential. Simply searching around the environment yields limited results, so you'll need to begin trading, planting, and peeing to exploit the game's economy to the fullest. At some point, I ran out of things to do while waiting for a new archaeological digs to open (yeah, that's a thing), but I didn't have enough money to buy the things I needed. The best way to hunt up currency is by searching trash cans every day, and the more you can do to increase the number of trash cans on your daily route, the richer you'll be. I reached a point in Crypt Worlds where for several in-game days I would do nothing but wake up, root through garbage all over town, and then go back to sleep. I felt like a dumpster diver looking for recyclable materials, which is something I've never felt in a game before. What begins as playful poking around eventually shifts to an ordered if not downright mundane process of scrounging for coin. I began to save urine for specific places where it furthered my progress too. For instance, if you pee on the detective, he'll drop gold bars, and peeing on bones after planting them will yield greater returns come harvest. It's screwy logic, but logic nonetheless.

Crypt Worlds has multiple endings depending on which special objects you've collected. Recover Goddess Moronia's relics and return them to her to face off against Dendygar or collect hidden crystals and take them to the Hellzone to summon the Chaos God. In my first playthrough, I went the chaos route, but unintentionally so. Maybe I wasn't paying close enough attention, but I had no idea that jumping down the literal hell hole with all of the crystals would trigger the irreversible series of events that follows. In retrospect, whether it was "good" or "bad," waking the Chaos God by accident definitely felt like the "right" ending. It was the game's way of throwing my arrogance back at me. "You think you've got this all figured out? Well, surprise!" With no saves states to reload, it's back to the beginning if you want to try for a different ending.

Crypt Worlds doesn't side with either order or chaos; it presents itself, and video games in general, as a battleground for the conflict. We "play" games, but that's different than being "at play." The disparity is partly that games tell you how to play instead of determining those constraints for yourself. In this way, game design itself can fit more in the realm of play than the actual experience of the game –a stance both reinforced and contested by the inclusion of the nerdy game making drones in Crypt Worlds' shadowy developer pit. The most out-there, freeform game design concepts are eventually called to order by demands of wieldable mechanical systems, and no matter how organized and polished your systems may be, they're still prone to be overturned by chaotic elements. This is the essence of Crypt Worlds, which truly is, in game development terms, your darkest desires, come true.

Friday, September 13, 2013

Recap: Ramiro Corbetta at NYU Poly

Last night at an event presented by Babycastles and NYU Poly's Game Innovation Lab, Hokra creator Ramiro Corbetta gave a talk about his thought process behind the game and his personal balance between designing and programming. This was followed by a conversation between Cobetta and NYU Professor Andy Nealen, and some questions from the audience. I'll embed video footage of the entire event once it's posted online (UPDATE: while not the full talk, NYU Poly Game Lab has produced a short video overview of the event).

The general dialogue focused heavily on how Corbetta delved into coding as a result of his frustration as a designer when he'd hand off projects to programmers and then they wouldn't come back exactly as he'd imagined. He explained this through the analogy of designing a sculpture where someone else actually does the chiseling for you. Corbetta got started with coding simply by picking up a how-to book and reading it cover to cover. After that it was all practice, trial and error, and working out problems with colleagues. If you're like me and don't know the differences between programming languages, some of the more entrenched moments between Nealen and Corbetta didn't make much sense, but the big lesson from the talk was still clear: if you're designing a game with action-based mechanics, you should learn how to code because that's where "gamefeel" is constructed.

Corbetta explained why with a simple multiplayer action game like Hokra, traditional game design scaffolding was only getting him so far. A game about passing and shooting a ball lives or dies by its execution, and that falls on the shoulders of the programmer. Hokra wouldn't get a pass on gameplay because of some new innovative design concept –it's 2-on-2 hockey. So, a lot rides on the coding side of things to make sure the game feels snappy and fun to play. As an example of an issue he had to solve through code, Corbetta spoke of a time when he was playtesting the game with some colleagues who felt that the direction that they were passing the ball in the game was not the direction they intended. Turns out this was an issue of timing and how quickly the human brain relays certain conclusions. The solution was to delay setting a direction for the ball for 3 frames after letting go of the "shoot" button, which makes the entire action feel more natural.

I'm consistently impressed by the diversity of talents that indie game makers must employ to achieve their holistic artistic vision. Its a deindustrializing maneuver that takes the tasks that are typically accomplished by separate teams, and sets that responsibility in the lap of one individual. The labor itself becomes something impressive, which sounds more in line with traditional art practice, but runs counter to the outsourcing production methods of many contemporary artists. In this way, indie game devs are sort of the microbreweries of the art world (they have the beards to prove it). While the quality of the final product remains of the utmost importance, the personality and homespun process behind it matter quite a bit too.

I remain extremely excited about the imminent release of Hokra on PS3 as part of the Sportsfriends package and will be curious to see what Corbetta gets up to once it and everything around their Kickstarter campaign is out the door.

Thursday, September 12, 2013

Blips: Excessive Motion

Source: The Body of the Gamer: Game Art and Gestural Excess

Author: Thomas Apperley

Site: Academia.edu from Taylor & Francis Online

OK, let's see how quickly I can break down this essay by professor Thomas Apperley about game art and human body glitch aesthetics. Putting aside whether video games are art, there exists game art, which is art that makes use of games in some fashion. This could be a straight-up art game, or it could be something else that makes use of the glitch, performance, or social aspects of games. The definition of game art is not simple to categorize and seems to be ever-expanding. Apperley's main focus is on motion controls and how they call more attention to the bodies of players than button-based interfaces do, and that the expressiveness of bodies at play using motion controls is ripe for implementation in game art, though not all that much game art has taken up this mantle. Apperley proposes that as far as game art is concerned, the human body acts as a glitch itself, though what he terms gestural excess. An example of gestural excess would be like when you're playing tennis in Wii Sports, and instead of performing a slight wrist flip to swing the virtual racket, you swing your entire arm as if you were actually playing a game out on a real court with real equipment. That excess motion is not factored into how the game interprets the controller motions, nor is your stance or your offhand. These are game behaviors, but they do not help players succeed in the game, and can in fact be detrimental to players' in-game success. Motion controls turn the role of glitch back onto the players when it comes to certain aspects of how the body interacts with games, but as these devices become more sophisticated and able to process minute gestural details, the window for gestural excess will begin to close.

How'd I do? I still recommend checking out the whole essay which cites a ton of neat examples of game art, most of which were new to me. I think Bennet Foddy's games fit into this discussion in an interesting way too, seeing as they get a lot of mileage out of the physicality of button pushing. A game like GIRP turns your computer keyboard into a timed game of Twister that you play with your fingers, and the ever-popular QWOP simultaneously simulates and abstracts muscular rhythms. I was a DDR player for a few years and definitely fell into the non-excessive "only do what's necessary" category, but not out of principle; I just wasn't good enough to have the time or energy to showboat. Then, when the Wii came out, dancing games that only tracked the Wiimote just seemed dumb. I couldn't understand why someone would dance an entire routine when the game only cares about the position of your right hand –too much excess.

Still, I worry that the time for game art to comment on these issues may be past us now. Wand-like motion controllers have fallen out of public favor, and only touchscreens and the new Kinect remain, the latter of which is attempting to cut out excess as much as possible, down to the minutiae of facial expressions. I fear we may have to wait until some kind of nostalgic reverence for the Wiimote emerges before we see game art of the sort of which Apperley identifies.

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

Blips: Games as Spaces

Source: Inflatable Maze-Like Sculpture Bathes People In Colored Light

Author: Sarah Brin

Site: The Creators Project

Level designers are the architects of video games. They create spaces for characters and mechanics to flourish and reflect back on those elements. Levels can evoke the personality of a setting and also educate the player on how to play the game. Level designers must consider how the spaces they create will guide players to move through the game and set expectations for what's possible. In a basic scenario, a character may have the ability to climb, but only on surfaces with dense woven textures like vines or netting. Once the player recognizes these as climbable surfaces, they'll seek out similar textures in other environments, expecting to be able to climb. Some games take a less prescriptive approach and are more sandbox-like in nature. Though they may also designate climbable surfaces in the same way, the spaces as a whole may not exclusively direct players toward climbing.

I found myself considering these open-purpose spaces after viewing pictures of Exxopolis, an inflatable luminarium most recently installed in a park in Los Angeles. Check the link above to Sarah Brin's article on the piece with accompanying pictures to get an idea of the sort of otherworldly space that exists inside Exxopolis. At what point is architecture level design, and at what point is architecture interactive art? The lines are blurred by projects like Exxopolis, which inspires exploration, meditation, and awe. Being an inflatable structure, visitors must remove their shoes, which has the added effect of evoking preparation for play, the same way children take off their shoes before entering a bouncy castle or a ball pit. The vibrant, tubular nature of the corridors is also reminiscent of tube mazes and the colored lighting effects of video games that were all the rage when that technology was new and in vogue. Small musical troupes also parade through Exxopolis at scheduled intervals, helping the environment to feel alive, and also providing a sort of soundtrack.

I can't speak from personal experience, since I've never visited Exxopolis, but it does remind me to some degree of the work of Ernesto Neto, whose cushy fabric caverns invite a similar degree of play. Likewise, I particularly enjoy level design in games that doesn't tell me what to do, but opens me up to play around and see what's possible.

:photo credit Simon Wiscombe:

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Blips: Downward Trend

Source: Game Over

Author: Horace Dediu, Dirk Schmidt

Site: Asymco

You may have run across this story on Kotaku yesterday, which links to some charts and analysis of Sony and Nintendo's video game console business by Horace Dediu and Dirk Schmidt for Asymco. The outlook for dedicated gaming devices looks bleak, but as Dediu notes, the numbers for the upcoming PS4 and Xbox One consoles haven't been added in, since they've yet to launch. Those two major console lanches could turn things around, but Dediu seems skeptical that either machine will achieve sales anywhere close to the Nintendo Wii, which saw an incredible mainstream crossover. Dediu attributes part of the downward market trend to increased prevalence and quality of smartphone games, which use devices that are multipurpose and most potential game console buyers already own.

I was struck by the conviction of so many commenters below the Asymco piece that fervently argue against this data. People who love games do not want to accept that their hobby is being co-opted by a bunch of touchscreen apps, but the statistics seem to say otherwise. Some commenters even brought up the just-announced PS Vita TV as a sign of hope for consoles, but it's much to early to project the impact of that currently-Japan-only device. For the record, I hope the new consoles do well and dedicated gaming machines continue to make sense. My only concern with touchscreen devices taking over is that currenty they're not ready to handle the demands met by gaming consoles, though they're not far off. If tablet PCs can easily hook up to televisions, support physical controllers, and also run graphically intensive games, then I'm all for it. While controllers and TV hookup are simple enough, computing power and storage will remain an issue for the time being.

Only time will tell, but, anecdotally speaking, I don't see game consoles lasting a generation beyond PS4 and Xbox One, but I do think the kinds of games that appear on those machines will continue to be made for popular devices. In the end, it's the games that matter, not the black box that runs them.

Monday, September 9, 2013

Blips: Annual Improvements

Source: The Truth Is Last Year's Games Had Problems. This Year's Are...Better?

Author: Stephen Totilo

Site: Kotaku

This inside look at the annual presentation of yearly sports titles shows the event to be as bizarre as it is routine. Basically a company like EA produces new sports simulation video games every year for every sport (recent basketball troubles notwithstanding), and so as part of the pitch for the new game, developers trot out the mistakes from the title that shipped fewer than 12 months ago and show how the most recent take improves the formula. The bottom line is supposed to be that every new game in a sports franchise is an improvement over the last one, not just the same game with roster updates, as has become the predominant accusation against EA's release strategy.

The GIF above is from Stephen Totilo's story and, though it took me a minute, I do see the difference between the two sides and the 2014 model does more accurately reflect how the human body moves when approaching a soccer ball for a kick. Is that change, and others like it, enough to justify paying another $60 year over year? Any game as complex as a sports simulation is going to have rough spots here and there, so I don't blame the developers for not achieving perfection and wanting to improve those facets with each iteration, but I also wonder how different FIFA 14 would be if there was no FIFA 13 and the team had double the usual time to produce it. Then again, they claim to focus on parts of the game where they've received feedback from players, so without an annual version of the game on the market, the developers are also missing out on certain criticisms.

With DLC the way it is now, annualized sports games seem ripe for the "service platform" model of updates. That is, you could buy a subscription of sorts to Madden Football and then instead of buying a totally new game next year, you get periodic updates as improved features roll out. In this model, simple animation "fixes" would be difficult to justify as purchasable content since it would likely fall under the "patch" category, and generally released for free. Right now though, the thirst for full-priced annual sports games has not let up, so there's not a strong business reason to change the format.

Ultimately I'm looking for an excuse to buy a new sports game since I stopped playing most of them once the Sega Genesis fell out of favor, save for a few soccer games here and there. Unfortunately, most new sports games seem to suck a lot of the fun out of the game at hand by hewing to evermore realistic simulation and TV presentation, both of which I care little about. Then again, as long as I can hand craft an entire team of create-a-characters, I'll at least be invested in my team, speaking as someone who doesn't follow professional sports very closely anymore. Maybe "silliness" could be a key addition to annual sports sims on next-gen consoles. In some old version of FIFA (don't remember the year) you could play in indoor arenas and one of the buttons was a straight-up two-armed shove. The most fun I've had with a soccer video game was turning off fouls and competing with my brother to see who could injure each others' entire rosters. Please, EA, bring this back! I can hear the presentations now, "Last year our game did not allow you to violently throw opposing players to the ground, but this year we've fixed all that by mapping that very action to the X button." *sigh* If only...

Friday, September 6, 2013

Blips: Neverending Finality

Source: Dispatches from A Realm Reborn

Author: Simon Parkin

Site: Eurogamer

Video games have been known to possess addictive qualities, and I like to think I've been able to show more restraint from falling into unhealthy gaming patterns as I've gotten older. MMOs always seemed to be the black tar heroin of addictive video games, and as such, I've steered clear of them, scared off by tales of lost time and disintegrating real world sociability. I've never wanted to subject myself to that sort of atmosphere. Whenever I hear MMO players discuss their experiences within these virtual worlds, they often seem intriguing, if not amazing, in concept, but I have trouble seeing past the grind of the actual moment-to-moment activities and the stunning time commitment.

Simon Parkin breaks down his mostly positive experience with Square-Enix's MMO reboot Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn in a recent piece for Eurogamer. The game does seem to have it's appeal, and the story behind it's development is incredible, and a bit heartbreaking. If ever I was to be swung over to the dark side and pick up an MMO, something with the Final Fantasy name attached to it might be the reason. Final Fantasy XII and Xenoblade Chronicles showed me that I actually enjoyed combat stylized with MMO trappings, but both of those games also have preconceived narratives with definitive endings, and, much to their credit, rarely pushed me to grind. Seeing series callbacks in FFXIV just makes me want to go back and play the older games in the series, not invest in a new title that also requires a monthly fee.

I want to like MMOs. The raids, the guilds, and the performative elements are all quite intriguing, but I've resolved to wait on the massively multiplayer structure until it breaks out of the World of Warcraft mold where it currently finds itself. If MMOs were for me, FFXIV might very well be my game, but since they're not, I'll continue to observe and appreciate from a safe distance.

Thursday, September 5, 2013

Blips: From Field to Screen

Source: Killer Queen: Half Joust, Half Starcraft and One Giant Snail

Author: Eric Blattberg

Site: Polygon

I've reached a point in my life where getting a local multiplayer game together with more than one friend is something that just doesn't happen anymore. The infrastructure of school is no longer there to act as a gathering force; the reason I enjoyed those games of 4-player Smash Bros Melee and split-screen Timesplitters in my freshmen dorm had everything to do with the human dynamics in the room. That's why a game like Killer Queen makes so much sense to me. The duo behind Killer Queen, Josh DeBonis and Nikita Mikros, originally made the RTS Joust game as a physical field game –like where you go outside and swing foam swords around. In fact, they even playtest the video game version in physical form to make sure it works. Starting from the angle of balancing not only mechanical attributes, but also physical group dynamics in a 10-person game is a strategy that seems perfectly apt.

I was introduced to Killer Queen by way of a profile by Eric Blattberg for Polygon, but will definitely be checking out next time I go to an NYU Game Center event, where the currently one-of-a-kind arcade cabinet is being housed. As is mentioned in the article, a college campus is an ideal environment for this kind of game, and I hope Josh and Nikita do end up pitching the cabinets to universities for placement in student unions, which would be ripe for school versus school network play, and, of course, local tournaments. It's something I feel like I would have been way into if there had been a machine on campus at my undergrad. I wish those guys the best of luck.

Oh, and since I've done a poor job of explaining what makes the actual game so special besides the uniqueness of it all, check out the article above or at least this video of competitive, yet fun and party-friendly play. And yes, root for the snail.

Wednesday, September 4, 2013

Blips: The Sporting Interface

Source: What can broadcast sports learn from videogames?

Author: Jason Johnson

Site: Kill Screen

The work happening over at Sportsvisionis fascinating stuff. Sportsvision is the company that invented many of the modern TV interface overlays for live sports coverage, including the yellow first down line in football and the constant mini-scoreboard in the corner of the screen in just about everything. In a recent article for Kill Screen, Jason Johnson points out how the relationship between sports TV broadcasting and live video game competitions could learn some things from one another.

However, history has shown that making sports more video game-y doesn't always go over so well. Remember the glow puck, which debuted in a brief stint in the 90s? It wasn't around for a long time because so many people found it distracting and made their complaints known. The glow puck was a Sportsvision invention too, but one that predated its use in games. On the surface, the glow puck is a genius idea, since it's often quite difficult to follow the tiny, laser-speed dot that is the puck in TV broadcasts. At the Twofivesix conference, former Sportsvision CEO Bill Squadron admitted that the glow puck technology wasn't refined enough to be as unobtrusive as viewers would have liked, but said that if a new glow puck were to be introduced that he feels the tech has advanced enough that it could be done right.

I'm all for more interfaces in sports TV since the technology is there and can be used in a way that enhances viewers' understanding of the action on screen. Plus, now that professional sports occupy so many of their own channels, why not give viewers the choice of two versions of the game? One with interface and one without. Or better still, take a cue from video games and include an options screen to turn on and off specific interface options at will. There are moves that could be made that would drive a whole new generation of people to be interested in sportscasting, the same way video game livestreams have stables of professional "casters" who are proficient in calling specific games. If new video game consoles want gamers to be more interested in using their machines to watch sports, they should consider giving them more control over the broadcasts.

Tuesday, September 3, 2013

Blips: Musical Landscape

Source: Listening to Proteus

Author: Daniel Golding

Site: Meanjin

I've written about Proteus at length on this blog, Kill Screen, and re/Action, and yet, as Daniel Golding proves in a recent piece for Meanjin, there's still more to say about the game. While there are plenty of interesting insights in Golding's piece, his comparison of Proteus to the work of composer John Luther Adams is the most striking. Adams lives and works in Alaska and has created a piece that is a kind of generative music system titled The Place Where You Go To Listen. I'd encourage you to check out the article for the fascinating full context, but essentially this piece is a musical installation that responds to live meteorological and seismological data by emitting accompanying tones and rumbles. Even the aurora borealis has it's own particular sound range, making every visitors' experience with the work different than those who came before.

While Adams' installation presents the "sounds of the earth," Proteus, as Golding points out, puts some of that compositional responsibility in the hands of the player. While we can assume raindrops in Proteus make the same jingly bell noises whether you're around to hear them or not, other sounds require action on the part of the player to bring them out –action like walking past a line of gravestones or chasing frogs and squirrels. You get to play a conductor of sorts in Proteus, except you walk around an island instead of waving a baton. Both Proteus and Adams' Place emphasize an ephemeral, performative quality to their musical compositions, but employ different methods of listener involvement.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)